[ Home ] [ Messages and Signs ] [ In Defense of the Truth ] [ Saints ] [ Pilgrimages ] [ Testimonies ] [ Ordering ]

|

GAMGOK CATHOLIC CHURCH Built in 1930, this is one of the most beautiful Catholic churches in Korea. A major pilgrimage site. by Robert Koehler on April 25, 2007

From Anseong, we (i.e., Andy Jackson and I) got on a bus to Janghowon in nearby Icheon-si. And from Janghowon, we walked across the river to its sister city, Gamgok-myeon, Eumseong-gun in lovely Chungcheongbuk-do.

Gamgok-myeon is home to one of Korea’s oldest—and certainly one of its most beautiful—Catholic churches, Gamgok Parish Church, or more precisely, Gamgok Maegoe Virgin Mary Catholic Cathedral (maegoe is the Sino-Korean word for the Rosary, so I guess the proper way to translate the name of the church—the English name of the official site not withstanding—would be Gamgok Our Lady of the Rosary Church).

Gamgok Parish Church sits atop a hill overlooking the town of Gamgok like a sentinel. The land where the church is now used to be the owned by Min Eung-sik, a second cousin of Empress Myeongseong and a major late Joseon-era conservative. During the Mutiny of 1882, when old-guard military units rebelled against the government’s military modernization plans, Min offered the empress sanctuary at his palatial home. After Empress Myeongseong’s assassination in 1895, Min was arrested and brought to Seoul. His home was occupied by loyalist militias, which made it a target of the Japanese Army, which proceeded to burn it down.

It’s said that when Bouillon first saw the massive house (presumably before the Japanese torched it) and the hillside on which it rested, he prayed that if the Virgin Mary were to give him the house and hill, he would become her humble servant, and she would be the patron saint of the church. Well, as it would turn out, the Blessed Virgin Mary held up her end of the bargain (and even got the Imperial Japanese Army to foot the cleanup bill), so Bouillon kept his, establishing a church in May 1896 and dedicating it to the Virgin Mary.

I’ll say this—Bouillon couldn’t have chosen a better spot to put a church. The place gives off a very happy, loving vibe. The church itself is absolutely beautiful—a red-and-black brick Gothic structure of the kind loved by French missionaries in Korea. It’s the surroundings, however, that make it what it is—how it looks out over the surrounding countryside, the beautiful trees that surround it, how you can feel the spring breeze. It’s just a very peaceful place.

Next to the church is the former priests’ residence.

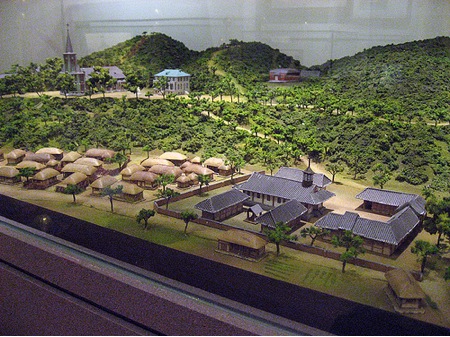

A beautiful stone building built in 1934, the residence alone would be worth a designation by the local cultural property authorities. The outside has been perfectly preserved, although the inside has been extensively remodeled for use as a museum/office/lounge/chapel—with emphasis on the museum. The museum is worth looking at—the church has done a fine job preserving its history, and there’s a lot to see inside.

I don’t recall how old this bell is, but I did find it fitting that a Catholic church would possess a bell that, except for the cherubs and cross, could be found in the main hall of just about any Buddhist temple. While Protestants and Buddhists have had a sometimes acrimonious relationship, Catholics and Buddhists have tended to get along much better. Interestingly, Catholicism was introduced to Korea sans not only missionaries, but also any real effort to bring the faith to the country:

One of the early converts to the faith was silhak guru Dasan Jeong Yag-yong, whose lists of accomplishment include the design of Suwon Hwaseong Fortress.

This brings us back to our intrepid French priest, Father Camillus Bouillon. Born in 1869, Bouillon dedicated his life to the Virgin Mary, which shouldn’t be a surprise given how he was raised not far from Lourdes. He came to Korea in 1893, immediately after entering the priesthood at the age of 33. He spend some 50 years in Korea—almost all of them in Gamgok, where he died in 1947. Oh, and he apparently had a thing for pith helmets. Which, of course, no white man should be without. Initially, he was buried on the hill in back of the church, but his remains have since been moved inside the church, near the altar. After his death, it appears the church struck up a relationship with the Maryknoll Fathers, with a number of American priests being sent to care for the flock.

Statue of Father Camillus Bouillon, Gamgok Cathedral Like a lot of French-built churches constructed in Korea, the interior uses pointed barrel vaults (ooo, pointed barrel vaults) above the nave.

The statue of the Virgin Mary in back of the altar, coincidentally, has seven bullet holes in it, courtesy the North Korean People’s Army. (Editor’s note: According to Fr. Anthony Jun, the current pastor of Gamgock Church, the North Korean Army officers entered this church to use it as their temporary quarters during their invasion of South Korea in the 1950s. They had trouble sleeping there, however, because of strange dreams that came back night after night. They finally noticed the Blessed Virgin Mary’s statue behind the altar and fired their automatic assault rifles at her, but the bullets could not destroy the statue, even though seven of the bullets made their marks on it, which, some say, signify the Seven Sorrows of the Blessed Mother. Then, the soldiers brought a ladder and climbed it to smash the statue with a hammer. When one of them was about to strike the statue, the Blessed Virgin suddenly stared down at him and also shed tears of blood from her eyes like a mother who scolds her disobedient children and weeps because of them. The soldiers were so frightened that they immediately left the Church. Several months later, after General MacArthur’s forces landed in Incheon and began their march to the north, the North Koreans began retreating and some of them passed the town of Gamgok again. While retreating, they forcefully took many young people with them, but, in Gamgok, they could not enter the church (because they remembered what had happened there before), and the young people hiding in the church were safe. Fr. Anthony Jun also said that, before the construction of the Catholic church in Gamgok, the Japanese completed builing a new Shinto shrine at the same location. Then, one day before celebrating the construction of the new shrine, a lightning from the clear sky destroyed the shrine. The Japanese were frightened, but built a larger and better shrine, but, again, a lightning out of the cloudless sky destroyed it on the day before celebrating the construction. The Japanese finally gave up. The current church was built in 1930 under the direction of Fr. Pierre Chizallet from France.)

On the other side of the church is a beautiful cloister adorned with the Stations of the Cross. The rock in the middle of the lawn, BTW, doesn’t have any particular meaning—it just looks nice.

As you can see, the place is a nice place to relax and shoot the breeze. The priest in the picture (Fr. Anthony Jun, Pastor), coincidentally, speaks fluent French, having spent many years in France.

And since everybody loves a pointed arch, here’s the view from the church entryway, out towards Gamgok. |

[ Home ] [ Messages and Signs ] [ In Defense of the Truth ] [ Saints ] [ Pilgrimages ] [ Testimonies ] [ Ordering ]