St.

Thérèse

of Lisieux

Virgin, Doctor of the Church

1897 (October 1)

From Lives of Saints

with Excerpts from their writings

Published by John J. Crawley & Co., Inc. New York,

Nihil Obstat: John M. A. Fearns, S.T.D., Censor Librorum

Imprimatur: +Francis Cardinal Spellman, Archbishop of New York

August 7, 1954

The spread of the cult of St. Thérèse of Lisieux is

one of the impressive religious manifestations of our time. During her

few years on earth this young French Carmelite was scarcely to be

distinguished from many another devoted nun, but her death brought an

almost immediate awareness of her unique gifts. Through her letters, the

word-of-mouth tradition originating with her fellow-nuns, and especially

through the publication of Histoire d'un âme, Thérèse of the Child

Jesus or "The Little Flower" soon came to mean a great deal to numberless

people; she had shown them the way of perfection in the small things of

every day. Miracles and graces were being attributed to her intercession,

and within twenty-eight years after death, this simple young nun had been

canonized. In 1936 a basilica in her honor at Lisieux was opened and

blessed by Cardinal Pacelli; and it was he who, in 1944, as Pope, declared

her the secondary patroness of France. "The Little Flower" was an admirer

of St. Teresa of Avila, and a comparison at once suggests itself. Both

were christened Teresa, both were Carmelites, and both left interesting

autobiographies. Many temperamental and intellectual differences separate

them, in addition to the differences of period and of race; but there are

striking similarities. They both patiently endured severe physical

sufferings; both had a capacity for intense religious experience; both led

lives made radiant by the love of Christ.

The parents of the later saint were Louis Martin, a

watchmaker of Alençon, France, son of an army officer, and Azélie-Marie

Guérin, a lace-maker of the same town. Only five of their nine children

lived to maturity; all five were daughters and all were to become nuns.

Françoise-Marie Thérèse, the youngest, was born on January 2, 1873. Her

childhood must have been normally happy, for her first memories, she

writes, are of smiles and tender caresses. Although she was affectionate

and had much natural charm, family was stricken by the sad blow of the

mother's death. Monsieur Martin gave up his business and established

himself at Lisieux, Normandy, where Madame Martin's brother lived with his

wife and family. The Guérins, generous and loyal people, were able to

ease the father's responsibilities through the years by giving to their

five nieces practical counsel and deep affection.

The Martins were now and always united in the closest

bonds. The eldest daughter, Marie, although only thirteen, took over the

management of the household, and the second, Pauline, gave the girls

religious instruction. When the group gathered around the fire on winter

evenings, Pauline would read aloud works of piety, such as the

Liturgical Year of Dom Gueranger. Their lives moved along quietly for

some years, then came the first break in the little circle. Pauline

entered the Carmelite convent of Lisieux. She was to advance steadily in

her religious vocation, later becoming prioress. It is not astonishing

that the youngest sister, then only nine, had a great desire to follow the

one who had been her loving guide. Four years later, when Marie joined

her sister at the Carmel, Thérèse desire for a life in religion was

intensified. Her education during these years was in the hands of the

Benedictine nuns of the convent of Notre-Dame-du-Prè. She was confirmed

there at the age of eleven.

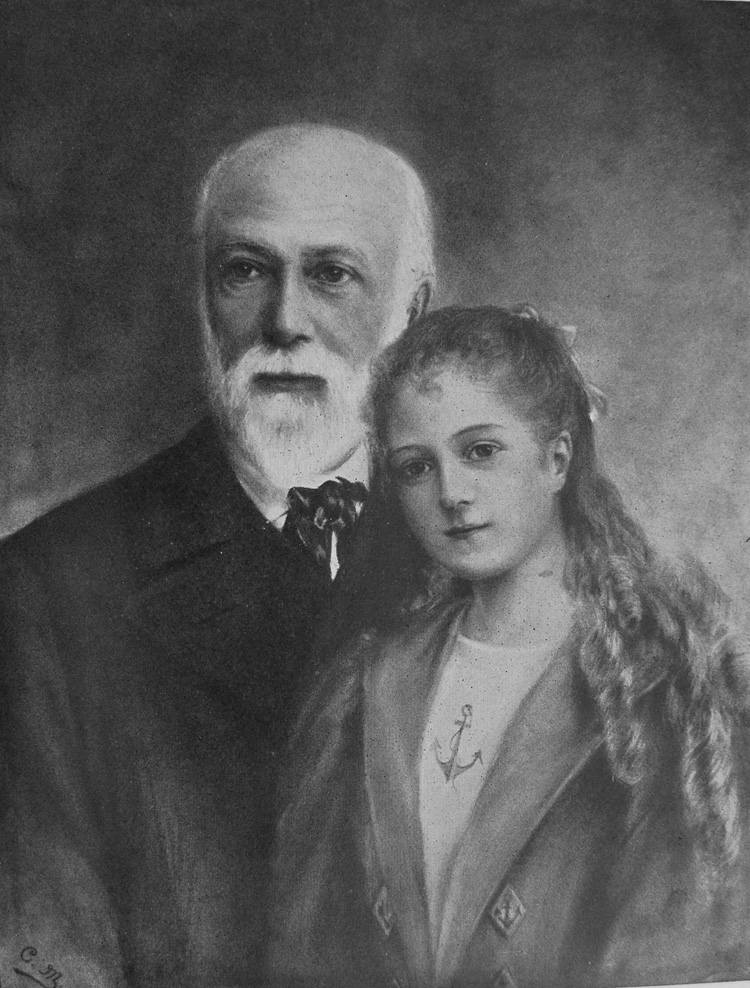

Thérèse and her mother

In her autobiography Thérèse writes that her

personality changed after her mother's death, and from being childishly

merry she became withdrawn and shy. While Thérèse was indeed developing

into a serious-minded girl, it does not appear that she became markedly

sad. We have many evidences of liveliness and fun, and the oral

tradition, as well as the many letters, reveal an outgoing nature, able to

articulate the warmest expressions of love for her family, teachers, and

friends.

On Christmas Eve, just a few days before Thérèse's

fourteenth birthday, she underwent an experience which she ever after

referred to as "my conversion." It was to exert a profound influence on

her life. Let her tell of it—and its moral effect—in her own words: "On

that blessed night the sweet infant Jesus, scarcely an hour old, filled

the darkness of my soul with floods of light. By becoming weak and

little, for love of me, He made me strong and brave: He put His own

weapons into my hands so that I went on from strength to strength,

beginning, if I may say so, 'to run as a giant.'" An indelible impression

had been made on this attuned soul; she claimed that the Holy Child had

healed her of undue sensitiveness and "girded her with His weapons." It

was by reason of this vision that the saint was to become known as "Thérèse

of the Child Jesus."

Thérèse (15 years old) and her

father, Louis

The next year she told her father of her wish to

become a Carmelite. He readily consented, but both the Carmelite

authorities and Bishop Hugonin of Bayeux refused to consider it while she

was still so young. A few months later, in November, to her unbounded

delight, her father took her and another daughter, Céline, to visit

Notre-Dame des Victoires in Paris, then on pilgrimage to Rome for the

Jubilee of Pope Leo XIII. The party was accompanied by the Abbé Reverony

of Bayeux. In a letter from Rome to her sister Pauline, who was now

Sister Agnes of Jesus, Thérèse described the audience: "The Pope was

sitting on a great chair; M. Reverony was near him; he watched the

pilgrims kiss the Pope's foot and pass before him and spoke a word about

some of them. Imagine how my heart beat as I saw my turn came: I didn't

want to return without speaking to the Pope. I spoke, but did not get it

all said because Mr. Reverony did not give me time. He said immediately:

'Most Holy Father, she is a child who wants to enter Carmel at fifteen,

but its superiors are considering the matter at the moment.' I would be

like to be able to explain my case, but there was no way. The Holy Father

said to me simply: 'If the good God wills, you will enter.' Then I was

made to pass on to another room. Pauline, I cannot tell you what I felt.

It was like annihilation, I felt deserted. . . . Still God cannot be

giving me trials beyond my strength. He gave me the courage to sustain

this one."

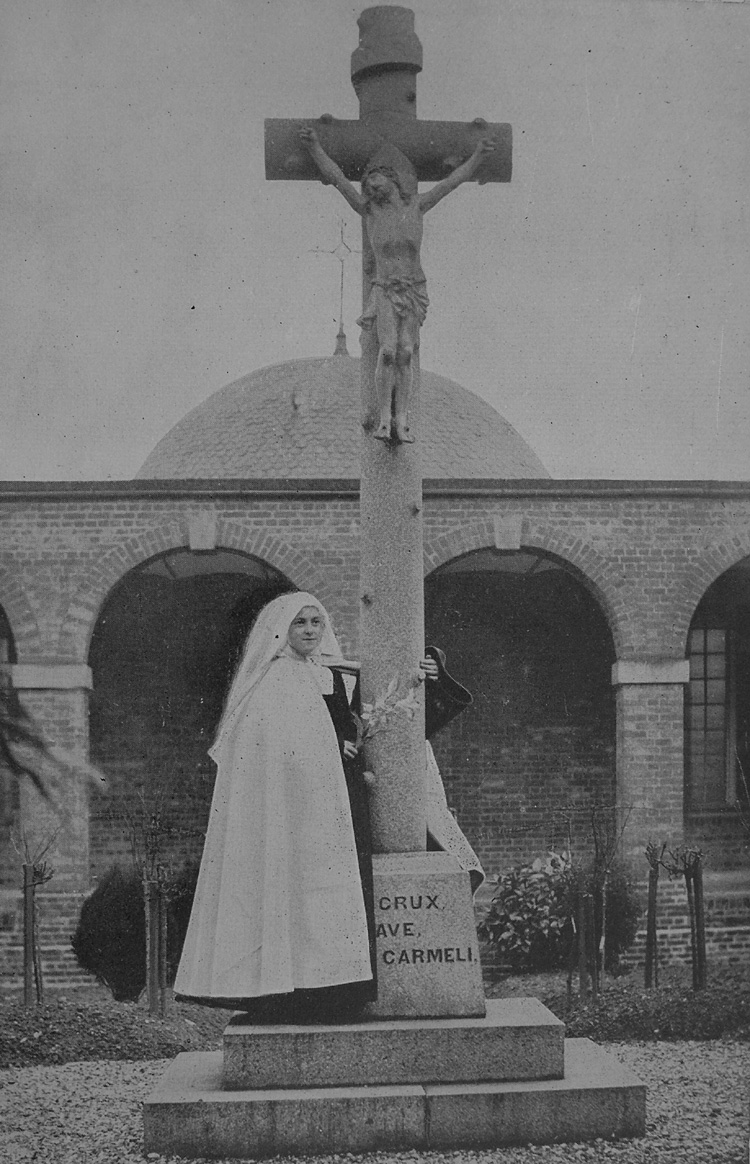

Thérèse of the Child Jesus,

novice at the Carmelite convent

(Age 16, January 1889)

Thérèse did not have to wait long in suspense. The

Pope's blessing and the earnest prayers she offered at many shrines during

the pilgrimage had the desired effect. At the end of the year Bishop

Hugonin gave his permission, and on April 9, 1888, Thérèse joined her

sisters in the Carmel of Lisieux. "From her entrance she astonished the

community by her bearing, which was marked by a certain majesty that one

would not expect in a child of fifteen." So testified her novice mistress

at the time of Thérèse's beatification. During her novitiate Father

Pichon, a Jesuit, gave a retreat, and he also testified to Thérèse's

piety. "It was easy to direct that child. The Holy Spirit was leading

her and I do not think that I ever had, either then or later, to warn her

against illusions. . . . What struck me during the retreat were the

spiritual trials through which God wished her to pass." Thérèse's

presence among them filled the nuns with happiness. She was slight in

built, and had fair hair, gray-blue eyes, and delicate features. With all

the intensity of her ardent nature she loved the daily round of religious

practices, the liturgical prayers, the reading of Scripture. After

entering the Carmel she began to sign letters to her father and others, "

Thérèse of the Child Jesus."

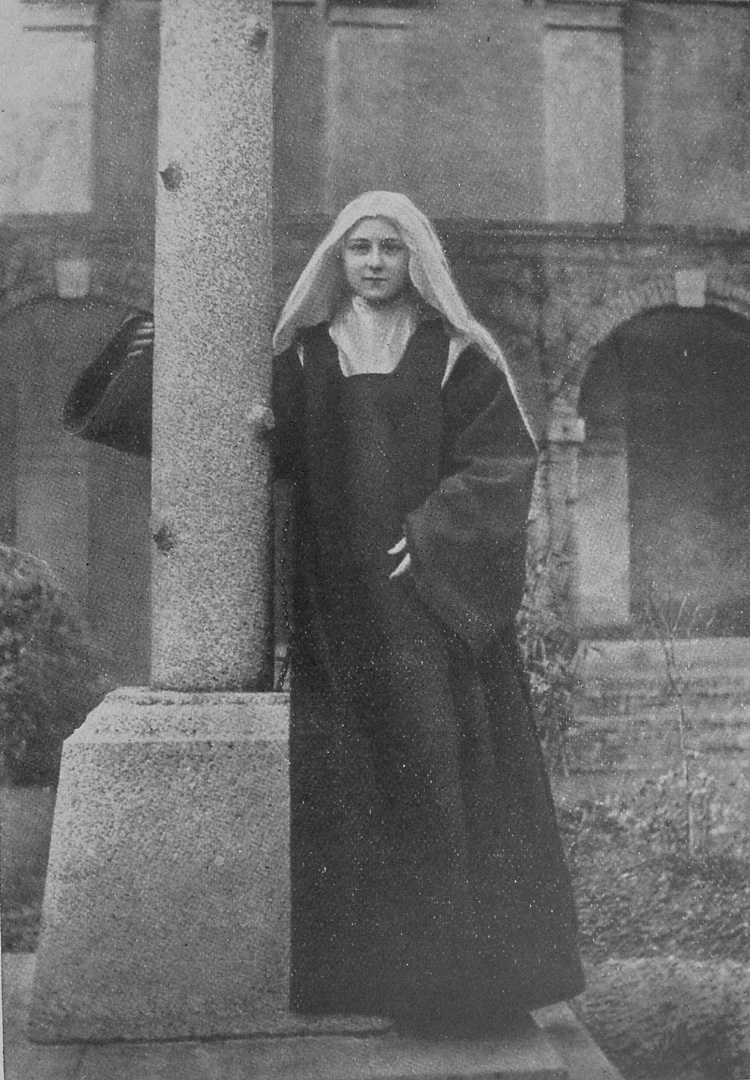

Thérèse of the Child Jesus, age 16

In 1889 the Martin sisters suffered a great shock.

Their father, after two paralytic strokes, had a mental breakdown and had

to be removed to a private sanitarium, where he remained for three years.

Thérèse bore this grievous sorrow heroically.

On September 8, 1890, at the age of seventeen,

Thérèse took final vows. In spite of poor health, she carried out from

the first all the austerities of the stern Carmelite rule, except that she

was permitted to fast. "A soul of such mettle," said the prioress, "must

not be treated like a child. Dispensations are not meant for her." The

physical ordeal which she felt more than any other was the cold of the

convent buildings in winter, but no one even suspected this until she

confessed it on her death-bed. And by that time she was able to say, "I

have reached the point of not being able to suffer any more, because all

suffering is sweet to me."

In 1893, when she was twenty, she was appointed to

assist the novice mistress, and was in fact mistress in all but name. She

comments, "From afar it seems easy to do good to souls, to make them love

God more, to mold them according to our own ideas and views. But coming

closer we find, on the contrary, that to do good without God's help is as

impossible as to make the sun shine at night."

In her twenty-third year, on order of the prioress,

Thérèse began to write the memories of her childhood and of life at the

convent; this material forms the first chapters of Histoire d'un âme,

the History of a Soul. It is a unique and engaging document,

written with a charming spontaneity, full of fresh turns of phrase,

unconscious self-revelation, and, above all, giving evidence of deep

spirituality. She describes her own prayers and thereby tells us much

about herself. "With me prayer is a lifting up of the heart, a look

towards Heaven, a cry of gratitude and love uttered equally in sorrow and

in joy; in a word, something noble, supernatural, which enlarges my soul

and unites it to God. . . . Except for the Divine Office, which in spite

of my unworthiness is a daily joy, I have not the courage to look through

books for beautiful prayers. . . . I do as a child who has not learned to

read, I just tell our Lord all that I want and he understands." She has

natural psychological insight: "Each time that my enemy would provoke me

to fight I behave like a brave soldier. I know that a duel is an act of

cowardice, and so, without once looking him in the face, I turn my back on

the foe, hasten to my Savior, and vow that I am ready to shed my blood in

witness of my belief in Heaven." She mentions her own patience

humorously. During meditation in the choir, one of the sisters

continually fidgeted with her rosary, until Thérèse was perspiring with

irritation. At last, "instead of trying not to hear it, which was

impossible, I set myself to listen as though it had been some delightful

music, and my meditation, which was not the 'prayer of quiet,'

passed in offering this music to our Lord." Her last chapter is a paean

to divine love, and concludes, "I entreat Thee to let Thy divine eyes rest

upon a vast number of little souls' I entreat Thee to choose in this world

a legion of little victims of Thy love." She counted herself among

these. "I am a very little souls, who can offer only very little things

to the Lord."

In 1894 Louis Martin died, and soon Céline, who had

of late been taking care of him, made the fourth sister from this family

in the Carmel at Lisieux. Some years later, the fifth Léonie, entered the

convent of the Visitation at Caen.

Thérèse occupied herself with reading and writing

almost up to the end of her life. That event loomed ever nearer as

tuberculosis made a steady advance. During the night between Holy

Thursday and Good Friday, 1896, she suffered a pulmonary hemorrhage.

Although her bodily and spiritual sufferings were extreme, she wrote many

letters, to members of her family and to distant friends, as well as

continuing Histoire d'un âme. She carried on a correspondence with

Carmelite sisters at Hanoi, Vietnam; they wished her to come out and join

them, not realizing the seriousness of her ailment. She had a great

yearning to respond to their appeal. At intervals moments of revelation

came to her, and it was then that she penned those succinct reflections

that are now repeated so widely. Here are three of them that give the

flavor of her mind: "I will spend my Heaven doing good on earth." I have

never given the good God aught but love, and it is with love that He will

repay." "My 'little way' is the way of spiritual childhood, the way of

trust and absolute self-surrender."

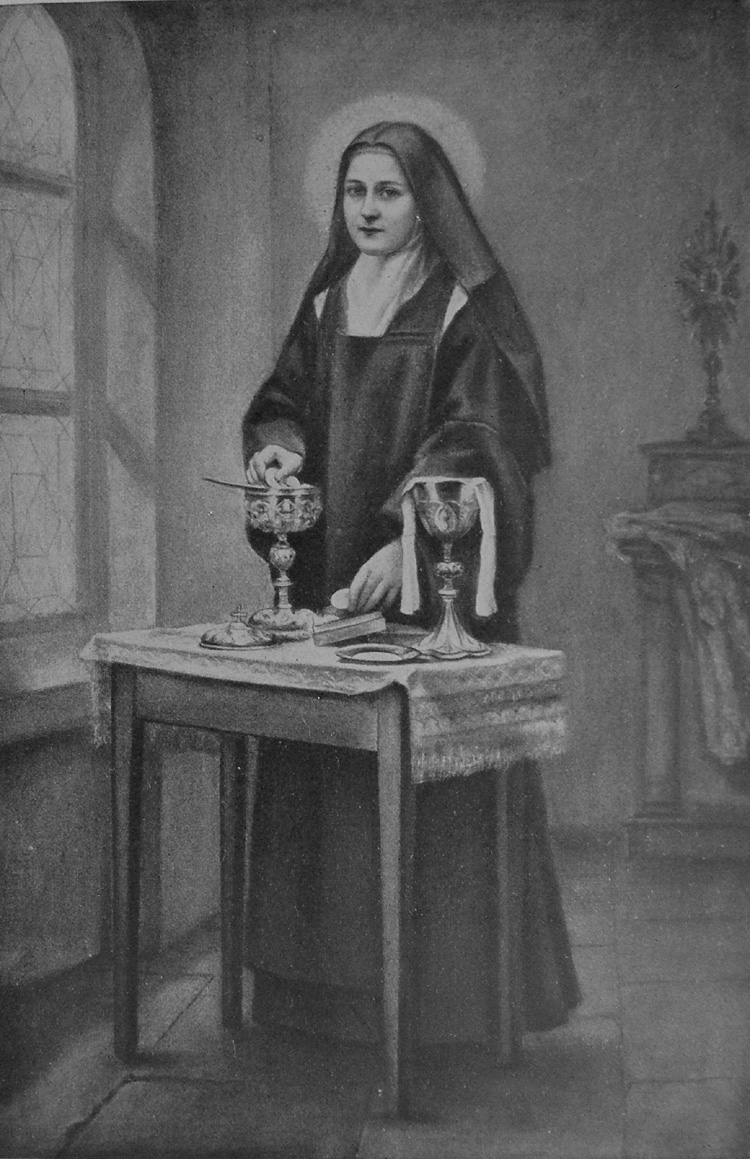

Thérèse of the Child Jesus

preparing the sacred vessels before Mass

(June 1896)

A further insight is given us in a letter Thérèse

wrote, shortly before she died, to Pére Roulland, a missionary in China.

"Sometimes, when I read spiritual treatises, in which perfection is shown

with a thousand obstacles in the way and a host of illusions round about

it, my poor little mind soon grows weary, I close the learned book, which

leaves my head splitting and my heart parched, and I take the Holy

Scriptures. Then all seems luminous, a single word opens up infinite

horizons to my soul, perfection seems easy; I see that it is enough to

realize one's nothingness, and give oneself wholly, like a child, into the

arms of the good God. Leaving to great souls, great minds, the fine books

I cannot understand, I rejoice to the little because 'only children, and

those who are like them, will be admitted to the heavenly banquet.'"

In June, 1897, Thérèse was removed to the infirmary

of the convent. On September 30, with the words, "My God . . . I love

Thee!" on her lips she died. The day before, her sister Céline, knowing

the end was at hand, had asked for some word of farewell, and Thérèse,

serene in spite of pain, murmured, "I have said all . . . all is

consummated . . . only love counts."

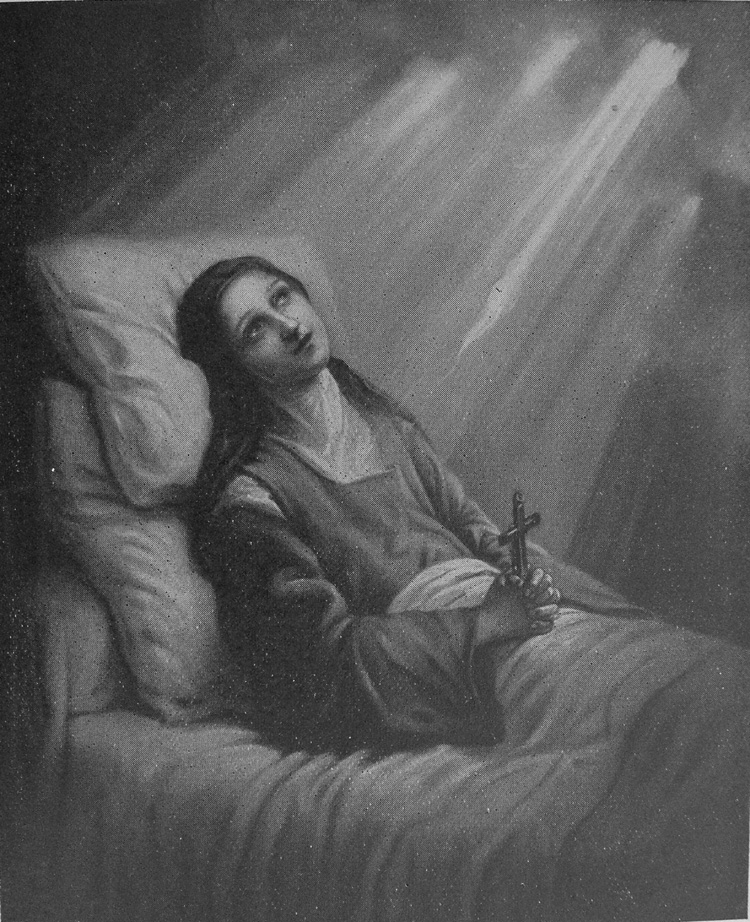

Thérèse of the Child Jesus

breathing her last (1897)

The prioress, Mother Marie de Gonzague, wrote in the

convent register, alongside the saint's act of Profession: ". . . The nine

and a half years she spent among us leave our souls fragrant with the most

beautiful virtues with which the life of a Carmelite can be filled. A

perfect model of humility, obedience, charity, prudence, detachment, and

regularity, she fulfilled the difficult discipline of mistress of novices

with a sagacity and affection which nothing could equal save her love for

God. . . . "

The Church was to recognize a profound and valuable

teaching in 'the little way'—connoting a realistic awareness of one's

limitations, and the wholehearted giving of what one has, however small

the gift. Beginning in 1898, with the publication of a small edition of

Histoire d'un âme, the cult of this saint of 'the little way' grew

so swiftly that the Pope dispensed with the rule that a process for

canonization must not be started until fifty years after death. Almost

from childhood, it seems Thérèse had consciously aspired to the heights,

often saying to herself that God would not fill her with a desire that was

unattainable. Only twenty-six years after her death she was beatified by

Pope XI, and in the year of Jubilee, 1925, he pronounced her a saint. Two

years later she was named heavenly patroness of foreign missions along

with St. Francis Xavier.

Basilica of St. Thérèse in Lisieux

|