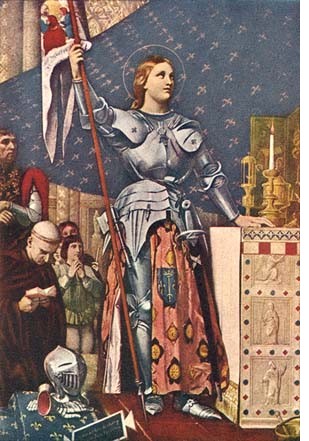

SAINT JOAN OF ARC

Virgin

Savior

of France and the national heroine of that country, Joan of Arc lives on

in the imagination of the world as a symbol of that integrity of purpose

that makes one die for what one believes. Jeanne la Pucelle, the Maid, is

the shining example of what a brave spirit can accomplish in the world of

men and events. The saint was born on the feast of the Epiphany, January

6, 1412, at Domremy, a village in the rich province of Champagne, on the

Meuse River in northeast France. She came of sound peasant stock. Her

father, Jacques d’Arc, was a good man, though rather morose; his wife

was a gentle, affectionate mother to their five children. From her the two

daughters of the family received careful training in all household duties.

"In sewing and spinning," Joan declared towards the end of her

short life, "I fear no woman." She whose destiny it was to save

France was a well-brought-up country girl who, in common with most people

of the time, never had an opportunity to learn to read or write. The

little we know of her childhood is contained in the impressive and often

touching testimony to her piety and dutiful conduct in the depositions

presented during the process for her rehabilitation in 1456, twenty-five

years after her death. Priests and former playmates then recalled her love

of prayer and faithful attendance at church, her frequent use of the

Sacraments, kindness to sick people, and sympathy for poor wayfarers, to

whom she sometimes gave up her own bed. "She was so good," the

neighbors said, "that all the village loved her." Savior

of France and the national heroine of that country, Joan of Arc lives on

in the imagination of the world as a symbol of that integrity of purpose

that makes one die for what one believes. Jeanne la Pucelle, the Maid, is

the shining example of what a brave spirit can accomplish in the world of

men and events. The saint was born on the feast of the Epiphany, January

6, 1412, at Domremy, a village in the rich province of Champagne, on the

Meuse River in northeast France. She came of sound peasant stock. Her

father, Jacques d’Arc, was a good man, though rather morose; his wife

was a gentle, affectionate mother to their five children. From her the two

daughters of the family received careful training in all household duties.

"In sewing and spinning," Joan declared towards the end of her

short life, "I fear no woman." She whose destiny it was to save

France was a well-brought-up country girl who, in common with most people

of the time, never had an opportunity to learn to read or write. The

little we know of her childhood is contained in the impressive and often

touching testimony to her piety and dutiful conduct in the depositions

presented during the process for her rehabilitation in 1456, twenty-five

years after her death. Priests and former playmates then recalled her love

of prayer and faithful attendance at church, her frequent use of the

Sacraments, kindness to sick people, and sympathy for poor wayfarers, to

whom she sometimes gave up her own bed. "She was so good," the

neighbors said, "that all the village loved her."

Joan’s early life, however, must have

been disturbed by the confusion of the period and the disasters befalling

her beloved land. The Hundred Years War between England and France was

still running its dismal course. While provinces were being lost to the

English and the Burgundians, while the weak and irresolute government of

France offered no real resistance. A frontier village like Domremy,

bordering on Lorraine, was especially exposed to the invaders. On one

occasion, at least, Joan fled with her parents to Neufchatel, eight miles

distant, to escape a raid of Burgundians who sacked Domremy and set fire

to the church, which was near Joan’s home.

The child had been three years old when

in 1415 King Henry V of England had started the latest chain of troubles

by invading Normandy and claiming the crown of the insane king, Charles

VI. France, already in the throes of civil war between the supporters of

the Dukes of Burgundy and Orleans, had been in no condition to resist, and

when the Duke of Burgundy was treacherously killed by the Dauphin’s

servants, most of his faction joined the British forces. King Henry and

King Charles both died in 1422, but the war continued. The Duke of

Bedford, as regent for the infant king of England, pushed the campaign

vigorously, one town after another falling to him or to his Burgundian

allies. Most of the country north of the Loire was in English hands.

Charles VII, the Dauphin, as he was still called, considered his position

hopeless, for the enemy even occupied the city of Rheims, where he should

have been crowned. He spent his time away from the fighting times in

frivolous pastimes with his court.

Joan was in her fourteenth year when she

heard the first of the unearthly voices, which, she felt sure, brought her

messages from God. One day while she was at work in the garden, she heard

a voice, accompanied by a blaze of light; after this, she vowed to remain

a virgin and to lead a godly life. Afterwards, for a period of two years,

the voices increased in number, and she was able to see her heavenly

visitors, whom she identified as St. Michael, St. Catherine of Alexandria,

and St. Margaret, the three saints whose images stood in the church at

Domremy. Gradually they revealed to her the purpose of their visits: she,

an ignorant peasant girl, was given the high mission of saving her

country; she was to take Charles to Rheims to be crowned, and then drive

out the English! We do not know just when Joan decided to obey the voices;

she spoke little of them at home, fearing her stern father’s

disapproval. But by May, 1428, the voices had become insistent and

explicit. Joan was sixteen, must first go quickly to Robert de Baudricourt,

who commanded the Dauphin’s forces in the neighboring town of

Vancouleurs and say that she was appointed to lead the Dauphin to his

crowning. An uncle accompanied Joan, but the errand proved fruitless;

Baudricourt laughed and said that her father should give her a whipping.

Thus rebuffed, Joan went back to Domremy, but the voices gave her no rest.

When she protested that she was a poor girl who could neither ride nor

fight, they answered, "It is God who commands it."

At last, she was impelled to return

secretly to Baudricourt, whose skepticism was shaken, for news had reached

him of just the sort of serious French defeat that Joan had predicted. The

military position was now desperate, for Orleans, the last remaining

French stronghold on the Loire, was invested by the English and seemed

likely to fall. Baudricourt now agreed to send Joan to the Dauphin, and

gave her an escort of three soldiers. It was her own idea to put on male

attire, as a protection. On March 6, 1429, the party reached Chinon, where

the Dauphin was staying, and two days later Joan was admitted to the royal

presence. To test her, Charles had disguised himself as one of his

courtiers, but she identified him without hesitation and, by a sign which

only she and he understood, convinced him that her mission was authentic.

The ministers were less easy to

convince. When Joan asked for soldiers to lead to the relief of Orleans,

she was opposed by La Tremouille, one of Charles’ favorites, and by

others, who regarded the girl either as a crazy visionary or a scheming

impostor. To settle the question, they sent her to Poitiers, to be

questioned by a commission of theologians. After an exhaustive examination

lasting for three weeks, the learned ecclesiastics pronounced Joan honest,

good, and virtuous; they counseled Charles to make prudent use of her

services. Thus vindicated, Joan returned full of courage to Chinon, and

plans went forward to equip her with a small force. A banner was made,

bearing at her request, the words, "Jesus, Maria," along with a

figure of God the Father, to whom two kneeling angels were presenting a

fleur-de-lis, the royal emblem of France. On April 27 the army left Blois

with Joan, now known to her troops as "La Pucelle," the Maid,

clad in dazzling white armor. Joan was a handsome, healthy, well-built

girl, with a smiling face, and dark hair which had been cut short. She had

now learned to ride well, but, naturally, she had no knowledge of military

tactics. Yet her gallantry and valor kindled the soldiers and with them

she broke through the English line and entered Orleans on April 29. Her

presence in the city greatly heartened the French garrison. By May 8 the

English fort outside Orleans had been captured and the siege raised.

Conspicuous in her white armor, Joan had led the attack and had been

slightly wounded in the shoulder by an arrow.

Her desire was to follow up these first

successes with even more daring assaults, for the voices had told her that

she would not live long, but La Tremouille and the archbishop of Rheims

were in favor of negotiating. However, the Maid was allowed to join in a

short campaign along the Loire with the Duc d’Alencon, one of her

devoted supporters. It ended with a victory at Patay, in which the English

forces under Sir John Falstolf suffered a crushing defeat. She now urged

the immediate coronation of the Dauphin, since the road to Rheims had been

practically cleared. The French leaders argued and dallied, and finally

consented to follow her to Rheims. There, on July 17, 1429, Charles VII

was duly crowned, Joan standing proudly behind him with her banner.

The mission entrusted to her by the

heavenly voices was now only half fulfilled, for the English were still in

France. Charles, weak and irresolute, did not follow up these auspicious

happenings, and an attack on Paris failed, mainly for lack of his promised

support and presence. During the action Joan was again wounded and had to

be dragged to safety by the Duc d’Alencon. There followed a winter’s

truce, which Joan spent for the most part in the company of the court,

where she was regarded with ill-concealed suspicion. When hostilities were

renewed in the spring, she hurried off to the relief of Compiegne, which

was besieged by the Burgundians. Entering the city at sunrise on May 23,

1430, she led a sortie against the enemy later in the day. It failed, and

through miscalculation on the part of the governor, the drawbridge over

which her forces were retiring was lifted too soon, leaving her and a

number of soldiers outside, at the mercy of the enemy. Joan was dragged

from her horse and led to the quarters of John of Luxembourg, one of whose

soldiers had been her captor. From then until the late autumn she remained

the prisoner of the Duke of Burgundy, incarcerated in a high tower of the

castle of the Luxembourgs. In a desperate attempt to escape, the girl

leapt from the tower, landing on soft tur, stunned and bruised. It was

thought a miracle that she had not been killed.

Never, during that period or afterwards,

was any effort made to secure Joan’s release by King Charles or his

ministers. She had been a strange and disturb ing ally, and they seemed

content to leave her to her fate. But the English were eager to have her,

and on November 21, the Burgundians accepted a large indemnity and gave

her into English hands. They could not take her life for defeating them in

war, but they could have her condemned as a sorceress and a heretic. Had

she not been able to inspire the French with the Devil’s own courage? In

an age when belief in witchcraft and demons was general, the charge did

not seem too preposterous. Already the English and Burgundian soldiers had

been attributing their reverses to her spells.

In a cell in the castle of Rouen to

which Joan was moved two days before Christmas, she was chained to plank

bed, and watched over night and day. On February 21, 1431, she appeared

for the first time before a court of the Inquisition. It was presided over

by Pierre Cauchon, bishop of Bauvais, a ruthless, ambitious man who

apparently hoped through English influence to become Archbishop of Rouen.

The other judges were lawyers and theologians who had been carefully

selected by Cauchon. In the course of six public and nine private

sessions, covering a period of ten weeks, the prisoner was cross-examined

as to her visions and voices, her assumption of male attire, her faith,

and her willingness to submit to the Church. Alone and undefended, the

nineteen-year-old girl bore herself fearlessly, her shrewd answers,

honesty, piety, and accurate memory often proving embarrassing to these

severe inquisitors. Through her ignorance of theological terms, on a few

occasions she was betrayed into making damaging statements. At the end of

the hearings, a set of articles was drawn up by the clerks and submitted

to the judges, who thereupon pronounced her revelations the work of the

Devil and Joan herself a heretic. The theological faculty of the

University of Paris approved the court’s verdict.

In final deliberations the tribunal

voted to hand Joan over to the secular arm for burning if she still

refused to confess she had been a witch and had lied about hearing voices.

This she steadfastly refused to do, though physically exhausted and

threatened with torture. Only when she was led out into the churchyard of

St. Ouen before a great crowd, to hear the sentence committing her to the

flames, did she kneel down and admit she had testified falsely. She was

then taken back to prison. Under pressure from her jailers, she had some

time earlier put off the male attire, which her accusers seemed to find

particularly objectionable. Now, either by her own choice or as the result

of a trick played upon her by those who wanted her death, she resumed it.

When Bishop Cauchon, with some witnesses, visited her in her cell to

question her further, she had recovered from her weakness, and once more

she claimed that God had truly sent her and that the voices had come form

Him. Cauchon was well pleased with this turn of events.

On Tuesday, May 29, 1431, the judges,

after hearing Cauchon’s report, condemned Joan as a relapsed heretic and

delivered her to the English. The next morning at eight o’clock she was

led out into the market place of Rouen to be burned at the stake. As the

faggots were lighted, a Dominican friar, at her request, held up a cross

before her eyes and, while the flames leapt higher and higher, she was

heard to call on the name of Jesus. Tressart, one of King Henry’s

secretaries, viewed the scene with horror and was probably joined in

spirit by others when he exclaimed remorsefully, "We are lost! We

have burned a saint!" Joan’s ashes were cast into the Seine.

Twenty-five years later, when the

English had been driven out, the Pope at Avignon ordered a rehearing of

the case. By that time Joan was being hailed as the savior of France.

Witnesses were heard and depositions made, and in consequence the trial

was pronounced irregular. She was formally rehabilitated as a true and

faithful daughter of the Church. From a short time after her death up to

the French Revolution, a local festival in honor of the Maid was held at

Orleans on May 8, commemorating the day the siege was raised. The festival

was reestablished by Napoleon I. In 1920 the French Republic declared May

8 a day of national celebration. Joan was beatified in 1909 and canonized

by Benedict XV in 1919.

— From Lives of Saints by John J. Crawley &

Co., 1954

|