St. Thomas Aquinas

Confessor, Doctor of the Church

1284

From Lives of Saints

with Excerpts from their writings

Published by John J. Crawley & Co., Inc. New York,

Nihil Obstat: John M. A. Fearns, S.T.D., Censor Librorum

Imprimatur: +Francis Cardinal Spellman, Archbishop of New York

August 7, 1954

The Italian family of Aquino traced its ancestry back

to the Lombard kings and was linked with several of the royal houses of

Europe. Landulph, father of Thomas Aquinas, held the titles of Count of

Aquino and Lord of Loreto, Acerro, and Belcastro; he was nephew of Emperor

Frederick Barbarossa and also connected to the family of King Louis IX of

France, whose life precedes this; his wife, Theodora, Countess of Teano,

was descended from the Norman barons who had conquered Sicily some two

centuries earlier. Thomas himself, at maturity, was a man of imposing

stature, massive build, and fair complexion, and appeared more of a

Norseman than a south Italian. The place and date of his birth are not

definitely known, but it is assumed that he was born in 1226 at his

father's castle of Roccasecca, whose craggy ruins are still visible on a

mountain which rises above the plain lying between Rome and Naples. He

was the sixth son in the family. While Thomas was still a child, his

little sister, who slept in the same room with him and their nurse, was

instantly killed one night by a bolt of lightning. This shocking

experience caused Thomas to be extremely nervous during thunderstorms all

his life long, and while a storm raged he often took refuge in a church.

After his death, there arose a popular devotion to him as a protector from

thunderstorms and sudden death.

A few miles to the south of Roccasecca,

on a high plateau, stands the most famous of Italian monasteries, Monte

Casino, the abbot of which, at the time, was Thomas' uncle. When he was

about nine years old the boy was sent to Cassino, in care of a tutor, to

be educated in the Benedictine school which adjoined the cloister. In

later years, when Thomas had achieved renown, the aged monks liked to

recall the grave and studious child who had pored over their manuscripts,

and who would ask them questions that revealed his lively intelligence and

his deeply religious bent. Thomas was popular too with his companions,

though he seldom took part in their games. He spent five happy years in

the school at Cassino, returning home now and again to see his parents.

On the advice of the abbot, when Thomas

had reached the age of fourteen, he went to the University of Naples to

begin the seven years' undergraduate course prescribed in all European

universities. He lived with his tutor, who continued to supervise his

life. Under a famous teacher, Peter Martin, Thomas went through the

Trivium, the three-year preliminary training in logic, rhetoric, and

grammar, which also included the study of Latin literature and Aristotle's

logic. This was followed by four years of the Quadrivium, which comprised

advanced work in mathematics, music, geometry, and astronomy or

astrology. In addition to these subjects, there was also some study of

physics under a celebrated scholar, Peter of Ireland, and extensive

reading in philosophy. It was then the custom for pupils to recapitulate

to the class a lecture they had just heard. Thomas' fellow students

observed that, when his turn came, the summary he gave was usually clearer

and better reasoned than the original discourse had been.

All this time Thomas was becoming more

and more attracted to the youthful Dominican Order, with its stress on

intellectual training. He attended its church and became friendly with

some of the friars. To the prior of the Benedictine house in Naples

Thomas confided his desire to become a Dominican. In view, however, of

the almost certain opposition of his family, the prior advised him to

foster his vocation, and wait for three years before taking any decisive

step. The passage of time only strengthened Thomas' determination, and

early in 1244, at the age of nineteen, he was received as a novice and

clothed in the habit of the Brothers Preachers.

News of the ceremony, which took place

before a large assemblage, was soon carried to Roccasecca. The members of

his family were indignant, not that Thomas had joined a religious

community, but that he, scion of a noble family, had chosen one of the

humble, socially scorned, mendicant orders. His mother, especially, had

expected that he would become a great churchman, possibly abbot of Monte

Cassino. Appeals were sent to the Pope and to the archbishop of Naples;

the Countess Theodora herself set out for Naples to persuade her son to

return home. The friars hurried Thomas off to their convent in Rome, then

sent him on to join the Father General of the Dominicans, who was leaving

for Paris. The countess now sent word to her other sons, who were serving

with the army in Tuscany, to waylay the fugitive. Thomas was overtaken as

he was resting at the roadside, and was forcibly brought back. He was

kept in confinement in the castle of San Giovanni. His sisters were

fallowed to visit him, and although they tried to undermine his

resolution, before long they were won over to his side, and secretly got

books for him from the friars at Naples. During his captivity Thomas

studied Aristotle's Metaphysics, Peter Lombard's Sentences,

and learned by heart long passages of the Bible. His brothers tried to

break his resistance by introducing into his room a woman of loose

character. Thomas seized a burning brand from the hearth and drove her

out, then knelt and implored God to grant him the gift of perpetual

chastity. His early biographers write that he at once fell into a deep

sleep, during which he was visited by two angels, who girded him around

the waist with a cord so tight that it waked him. Thomas himself did not

reveal this vision, until, on his deathbed, he described it to his old

friend and confessor, Brother Reginald, adding that from this time on he

was never again troubled by temptations of the flesh.

At last, influenced by the remonstrances

that came from both the Pope and the Emperor, his family began to yield.

A band of Dominicans hurried in disguise to the prison, where, we are

told, with the help of his sisters, Thomas was let down by a cord into

their arms, and they took him joyfully to Naples. The following year he

made his full profession there, before the prior who had first clothed him

with the habit of St. Dominic. Somewhat later, the powerful Aquino family

obtained from Pope Innocent IV permission to have Thomas appointed abbot

of Monte Cassino without resigning his Dominican habit. When Thomas

declined this honor, the Pope expressed a willingness to promote him to

the archiepiscopal of Naples, but the young man made clear his

determination to refuse all offices.

The Dominicans now decided to send Thomas

to Paris to complete his studies under their great teacher, Albertus

Magnus, and he set out on foot with the Father General, who was again on

his way northward. Carrying only their breviaries and their satchels,

they made their way over the Alps in midwinter, and trudged first to

Paris, and then, it is thought, on to Cologne, where Albertus was

lecturing. The schools there were full of young clerics from all corners

of Europe, eager to learn and discuss. The humble, reserved newcomer was

not immediately appreciated by students or professors. In fact, his

silence at disputations and his bulky figure won him the name of "the dumb

Sicilian ox." A fellow student, out of pity for his apparent dullness,

offered to explain the daily lessons, and Thomas thankfully accepted. But

when they came to a difficult passage which baffled the would-be teacher,

he was amazed when his pupil explained it clearly. Albertus once asked

his pupils for their views on obscure passage in the mystical treatise,

The Book of Divine Names, by the ancient author known as Dionysius the

Areopagite. Albertus was struck by the brilliance of Thomas'

explanation. The next day he questioned Thomas in public and at the close

exclaimed, "We have called Thomas 'dumb ox,' but I tell you his bellowing

will yet be heard to the uttermost parts of the earth." He forthwith had

the young man moved to a cell beside his own, took him on walks, and

invited him to draw on his own stores of knowledge. It was at this period

that Thomas began his commentary on the Ethics of Aristotle.

The general chapter, which decreed that

Albertus should go to Paris to take the degree of Doctor and occupy a

chair in the university, arranged that Thomas should accompany him. They

set out, on foot, as always; they ate by the roadside the food given them

in charity, and slept wherever they found shelter, or even under the

stars. At the Dominican convent in Paris Thomas proved himself an

exemplary friar, excelling in humility as he did in learning. Albertus

drew such crowds to his lectures that he had to deliver them in a public

square. It is likely that Thomas was always present. He made one

intimate friend in Paris, a Franciscan student, later to be known to the

world as St. Bonaventura, the "Seraphic Doctor," as Thomas was to be the

"Angelic Doctor." The two seemed to complement each other perfectly.

Bonaventura was the elder by four years, but they were at the same stage

in their studies, and both received the degree of Bachelor of Theology in

1248.

That same year Albertus went back to

Cologne, accompanied by Thomas, who lectured under him, and, as a

Bachelor, supervised the students' work, corrected their essays, and read

with them. Thomas exhibited a marvelous talent for imparting knowledge.

After he had received Holy Orders from the archbishop of Cologne, his

religious fervor became more marked. One of his biographers writes, "When

consecrating at Mass, he would be overcome by such intensity of devotion

as to be dissolved in tears, utterly absorbed in its mysteries and

nourished with its fruits." It was at this period that he became

celebrated as a preacher, and his sermons in the German vernacular

attracted enormous congregations. He was also occupied writing

Aristotelian treatises and commentaries on the Sciptures. In the autumn

of 1252, Thomas returned to Paris to study for his doctorate. On the way

he preached at the court of the Duchess of Brabant, who had requested his

advice on how to treat the Jews in her dominion. He wrote for her a

dissertation urging humanity and tolerance.

Academic degrees were then conferred for

the most part only on men actually intending to teach. To become a

Bachelor a man must have studied at least six years and attained the age

of twenty-one; to be a Master or a Doctor, he must have studied eight more

years and be thirty-five years of age. But when Thomas in 1252 began

lecturing publicly in Paris, he was not yet twenty-eight.

The popularity of the lectures of the

young Dominican inflamed a situation which was already acute. The secular

or non-monastic clergy, who from the early years of the universities had

furnished the bulk of the teaching staffs, saw dangerous rivals in the

eloquent and popular young friar preachers, who were often less

conventional in their methods and approach. They appealed to Rome to

forbid the intrusion of either Franciscans or Dominicans into what they

regarded as their particular preserve, and Innocent IV in 1254 withdrew

all favor from the two orders. However, he died at about this time and

his successor, Alexander IV, was to prove friendly to the friars. The

opposition to their admission to teaching posts in the universities grew

even more bitter with the publication of a libelous tract, On the

Dangers of These Last Times, by William de Saint-Armour, in which both

the ideas and the organization of the mendicant orders were denounced.

Representatives of the two orders were now summoned to Rome, Thomas being

chosen as one of the Dominican delegates. He pleaded with such success

that the decision was given in their favor. The Pope now compelled the

university authorities to admit Thomas and Bonaventura to positions as

teachers and to the degree of Doctor of Theology. This was in October,

1257, when Thomas was thirty-two years old.

From 1259 to 1269 Thomas was in Italy

teaching in the school for select students attached to the papal court,

which accompanied the Pope through all his changes of residence. As a

consequence, he lectured and preached in many Italian towns. In 1263 he

probably visited London as representative from the Roman province at the

general chapter of the Dominican Order. In 1269 he was back again for a

year or two in Paris. By then King Louis IX held him in such esteem that

he consulted him on important matters of state.

The university referred to him a question

on which the older theologians were themselves divided, namely, whether,

in the Sacrament of the altar, the accidents remained in reality in the

consecrated Host, or only in appearance. After much fervent prayer,

Thomas wrote his answer in the form of a treatise, still preserved, and

laid it on the altar before offering it to the public. His decision was

accepted by the university and afterwards by the whole Church. On this

occasion we first hear of his receiving the Lord's approval of what he had

written. Appearing in a vision, the Savior said to him, "Thou hast

written well of the Sacrament of My body," whereupon, it is reported,

Thomas passed into an ecstasy and remained so long raised in the air that

there was time to summon many of the brothers to behold the spectacle.

Again, towards the end of his life, when at Salerno he was laboring over

the third part of his great treatise, Against the Pagans (Summa Contra

Gentiles), dealing with Christ's Passion and Resurrection, a sacristan

saw him late one night kneeling before the altar and heard a voice,

coming, it seemed, from the crucifix, which said, "Thou has written well

of Me, Thomas; what reward wouldst thou have?" To which Thomas replied,

"Nothing but Thyself, Lord."

After his second period of teaching in

Paris he was recalled to Rome, and from there was sent, in 1272, to

lecture at the University of Naples, in his home city. On the feast of

St. Nicholas the following year, as he said Mass in the convent, he

received a revelation which so overwhelmed him that he never again wrote

or dictated. He put aside his chief work, the Summary of Theology

(Summa Theologica), still incomplete. To Brother Reginald's anxious

query, he replied, "The end of my labors is come. All that I have written

seems to me so much straw after the things that have been revealed to me."

He was already ill when he was

commissioned by the Pope to attend the general council at Lyons, which had

for its business the discussion of the reunion of the Greek and Latin

Churches. He was to bring with him his treatise, Against the Errors of

the Greeks. On the way he became so much worse that he was taken to

the Cistercian abbey of Fossa Nuova near Terracina. Yielding to the

entreaties of the monks, he began to expound the "Song of Songs," but was

unable to finish the interpretation. He made his confession to Brother

Reginald, received the Viaticum from the abbot, repeated aloud his own

beautiful hymn, "With all my soul I worship Thee, Thou hidden Deity," and

in the early hours of March 7, 1274, gave up his spirit. He was only

forty-eight years of age. On that day his old master, Albertus Magnus,

then in Cologne, burst suddenly into tears in the midst of the community,

and exclaimed: "Brother Thomas Aquinas, my son in Christ, the light of the

Church, is dead! God has revealed it to me."

Thomas was canonized by Pope John XXII at

Avignon, in 1323. In 1367 the Dominicans got possession of his body and

translated it with great pomp to Toulouse, where it still lies in the

Church of St. Sernin. Pope Pius V conferred on Thomas the title of Doctor

of the Church, and Leo XIII, in 1880, declared him the patron of all

Catholic universities, academies, colleges, and schools. Among his

emblems are the following: ox, chalice, dove, and monstrance.

On his writings, which fill twenty

volumes, we cannot here speak at length. As a philosopher, the great

contribution of Aquinas was his use of the works of Aristotle to build up

a rational and ordered system of Christian doctrine, his method of

exposition and proof being scientific and lucid. He would first state the

problem or question under consideration, next, one by one, fairly and

objectively, the arguments against his own point of view, often citing the

authorities on which they rested. Then came a statement of his own

position with the arguments to support it, and, finally, one by one, the

answers to his opponents. The general tone of his arguments was

invariably judicial and serene. To him faith and reason could never be

contradictory, for they both came from the one source of all truth, God,

the Absolute One. The most important of his books were the Summa

Theologica and the Summa Contra Gentiles, which were written

between 1265 and 1272. Together they form the fullest and most exact

exposition of Catholic dogma yet gives to the world. Over the former he

labored for five years, and left it, as we have said, unfinished. Almost

at once it was recognized as the greatest intellectual achievement of the

period. Three centuries later, at the momentous Council of Trent, this

work was one of the three authoritative sources of Catholic faith laid

down before the assembly, the other two being the Bible and the Decretals

of the Popes. No theologians save Augustine has had so much influence on

the Western Church as the "Angelic Doctor."

His work was not confined to the fields

of dogma, apologetics, and philosophy. When Pope Urban IV decided to

institute the Feast of Corpus Christ, he asked Thomas to compose a

liturgical office and Mass for the day. These are remarkable both for

their doctrinal accuracy and their tenderness of feeling. Two of his

hymns, the "Verbum Supernum" ("Word on High") and "Pange Lingua"

("Sing my Tongue") are familiar to all Catholics, because their final

verses are regularly sung at Benediction; but there are others, notably

the "Lauda Sion" ("Praise Zion") and the "Adoro Te Devote"

("With all my Soul I Worship Thee"), hardly less popular.

About his attainments Thomas was

singularly modest. Asked if he were never tempted to pride, he replied,

"No." If any such thoughts occurred to him, he said, his common sense

immediately dispelled them by showing him their absurdity. He was always

apt to think others better than himself, and never was he known to lose

his temper in argument, or to say anything unkind. As a young friar in

Paris, he was once mistakenly corrected, by the official corrector, while

reading aloud the Latin text for the day in the refectory. He accepted

the emendation and pronounced what he knew to be a false quantity. On

being asked afterwards how he could consent to make so obvious a blunder,

he replied, "It matters little whether a syllable be long or short, but it

matters much to practice humility and obedience."

During a stay in Bologna, a lay brother

who did not know him ordered him to accompany him to the town where he had

business to transact. The prior, it seemed, had told him to take as

companion any brother he found disengaged. Thomas was lame and although

he was aware that the brother was making a mistake, he followed him at

once, and took several scoldings for walking so slowly. Later the lay

brother discovered his identity, and was overcome with self-reproach. To

his abject apologies Thomas replied simply, "Do not worry, dear brother. .

. . I am the one to blame. . . . I am only sorry I could not be more

useful." When others asked him why he had not explained who he was, he

answered: "Obedience is the perfection of the religious life; for by it a

man submits to man for the love of God, even as God made Himself obedient

to men for their salvation."

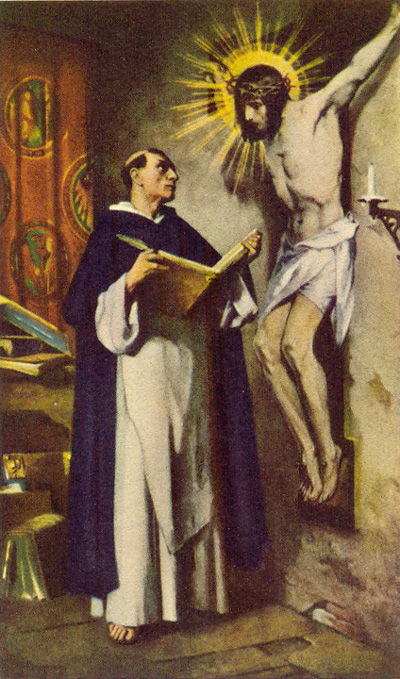

St. Thomas Aquinas beholding the

crucified Christ in a vision

The Goodness of God

(Question

6)

First Article. Whether goodness belongs to God?

We proceed thus to the First Article:—

Objection I. It

seems that goodness does not belong to God. For goodness consists in

limit, species and order. But these do not seem to belong to God, since

God is vast and not in the order of anything. Therefore goodness does not

belong to God.

Obj. 2. Further, the

good is what all things desire. But all things do not desire God, because

all things do not know Him; and nothing is desired unless it is known.

Therefore goodness does not belong to God.

On the contrary, It

is written (Lamentations iii, 25): The Lord is good to them that hope in

Him, to the soul that seeketh Him.

I answer that,

Goodness belongs pre-eminently to God. For a thing is good according to

its desirableness. And everything seeks after its own perfection, and the

perfection and form of an effect consists in a certain likeness to its

cause, since every cause creates its like. Hence the cause itself is

desirable and has the nature of a good. The thing desirable in it is a

participation in its likeness. Therefore, since God is the first

producing cause of all things, it is plain that the aspect of good and of

desirableness belong to Him; and hence Dionysius attributes goodness to

God as to the first efficient cause, saying that "God is called good as

the One by Whom all things subsists."

Reply Obj. I. To

have limit, species, and order belongs to the essence of a caused good;

but goodness is in God as in its cause; hence it belongs to Him to impose

limit, species, and order on others; wherefore these three things are in

God as in their cause.

Reply Obj. 2. All

things, by desiring their own perfection, desire God Himself, inasmuch as

the perfections of all things are so many approaches to the divine being,

as appears from what is said above. Of those beings that desire God, some

know Him as He is in Himself, and this is true of the rational creature;

others know some participation in His goodness, and this belongs to sense

knowledge; and others have a natural desire, but without knowledge, and

are directed to their ends by a higher knower.

The Cause of Evil

(Question

49)

Second Article: Whether the Highest Good, God, is

the Cause of Evil?

We proceed thus to the Second Article:—

Objection I. It

would seem that the highest good, God, is the cause of evil. For it is

said (Isaiah xlv, 5, 7): I am the Lord, and there is no other God,

forming the light and creating the darkness, making peace and creating

evil. It is also said (Amos iii, 6), Shall there be evil in a city which

the Lord hath not done?

Obj. 2. Further, the

effect of a secondary cause is attributable to its first cause. But good

is the cause of evil, as was said above. Therefore, since God is the

cause of every good, as was shown above, it follows that every evil also

is from God.

Obj. 3. Further, as

the Philosopher says, the cause of both the safety and the danger of a

ship is the same. But God is the cause of the safety of all things.

Therefore He is the cause of all destruction and of all evil.

On the contrary,

Augustine says that, "God is not the author of evil, because He is not the

cause of the tendency to cease from being."

I answer that, As

appears from what has been said, the evil which consists in defective

action is caused always by the defect of the agent. But in God there is

no defect but the highest perfection, as was shown above. Hence the evil

which consists in defective action, or which is caused by defect in the

agent, is not attributable to God as its cause.

But the evil which consists

in the corruption of things is attributable to God as its cause. And this

seems true as regards both things of nature and creatures with will. For

we have said that whenever an agent produces by its power a form which is

followed by corruption and decay, it causes by its power that corruption

and decay. Now clearly the form which God chiefly intends in created

things is the good of the order of the universe. But the order of the

universe requires, as was said above, that there should be some things

that can, and sometimes do, fail. Thus God, by causing in things the good

of the order of the universe, consequently, and as it were incidentally,

causes corruptions in things, in accordance with I Kings ii, 6: The Lord

killeth and maketh alive.

And when we read that God

hath not made death (Wisdom I, 13), the meaning is that God does not will

death for its own sake. Yet the order of justice too belongs to the order

of the universe; and this requires that penalty should be dealth out to

sinners. Thus God is the author of the evil which is penalty, but not of

the evil which is fault, by reason of what we have said.

Reply Obj. I. These

passages refer to the evil of penalty, and not to the evil of fault.

Reply Obj. 2. The

effect of a defective secondary cause is attributable to its first

non-defective cause as regards what it contains of being and perfection,

but not as regards what it contains of defect; just as whatever there is

of movement in the act of limping is caused by a motive energy, whereas

whatever is unbalanced in it does not come from the motive energy but from

the curvature of the leg. So whatever there is of being and action in a

bad act is attributable to God as the cause; and whatever there is of

defect is not caused by God but by the defective secondary cause.

Reply Obj. 3. The

sinking of a ship is attributed to the pilot as its cause since he does

not perform what the safety of the ship requires; but God does not fail to

do what is necessary for our safety. Hence there is no comparison.

(Summa

Theologica, I.)

|