[ Home ] [ Messages and Signs ] [ In Defense of the Truth ] [ Saints ] [ Pilgrimages ] [ Testimonies ] [ Ordering ]

|

OUR LADY OF GUADALUPE Reprinted from an article by Lester Mark Haddad, M. D.

¿No estoy aquí, yo, que soy tu madre? Am I not here, who am your Mother? Are you not under my shadow and protection? Am I not the fountain of your joy?

The appearance of Our Lady of Guadalupe to the Aztec Indian Juan Diego in December of 1531 generated the conversion of Mexico, Central and South America to Catholicism. Indeed, the Blessed Virgin Mary entered the very lifestream of Central America and became an inextricable part of Mexican life and a central figure to the history of Mexico itself. The three most important religious celebrations in Central and South America are Christmas, Easter, and December 12, the feast-day of Our Lady of Guadalupe. Her appearance in the center of the American continents has contributed to the Virgin of Guadalupe being given the title "Mother of the Americas." 1-3

THE SETTING It is important to understand the historical background and setting at the time of the apparition to fully appreciate the impact of the Virgin of Guadalupe, La Morenita, as she is affectionally known to the Mexican people.

The Aztecs The Aztecs ruled most of Central America in 1500, and their Empire known as Mesoamerica extended from the Gulf of Mexico to the Pacific Ocean and included the lands of Mexico, Guatamala, Belize, and portions of Honduras and El Salvador. Montezuma (or Moctezuma) the Younger, considered the earthly representative of the sun god Huitzilopochtli, became King of the Aztecs in 1503, and ruled from the capital Tenochtitlan and its sister-city Tlatelolco, both situated on an island in Lake Texcoco, the site of modern Mexico City. The inhabitants of the island were called the Mexica. 4-5 Montezuma demanded heavy tribute from the surrounding Indian tribes, and was poised to conquer the few remaining regions of the dying Mayan civilization. The city of Tenochtitlan was the center of religious worship for the Aztecs. Since the Mexica believed that the gods required human blood to subsist, the priests sacrificed thousands of living humans a year, generally captured Indians from surrounding tribes, in order to appease the frightful deities. 4-7 Two gods important to understanding the events of history were Quetzelcoatl, the stone serpent, and Tonantzin, the mother god. Quetzelcoatl was the god who founded the Aztec nation, but left when human sacrifice began, as he was opposed to the terrible ritual; but he vowed to return one day to reclaim his throne and redeem the Aztecs in the year 1-Reed, which occurred every 52 years in the Aztec time cycle. Tonantzin was depicted as a terrifying figure, with her head comprised of snakes and her garment a mass of writhing serpents; her eyes projected fathomless grief. Tonantzin was worshipped at a stone temple in Tepeyac, about five miles from the capital Tenochtitlan. Montezuma's sister, Princess Papantzin, lapsed in a coma in 1509. Upon her recovery, she related a dream that profoundly influenced the superstitious King. In her dream a luminous being with a black cross on his forehead led her to a shore with large ships that would come to their shores to conquer the Aztecs and bring them the true God. It was only ten years later, in the year 1-Reed, a year when Quetzelcoatl could return, that the Conquistadors of Spain arrived on the shores of Mexico.2

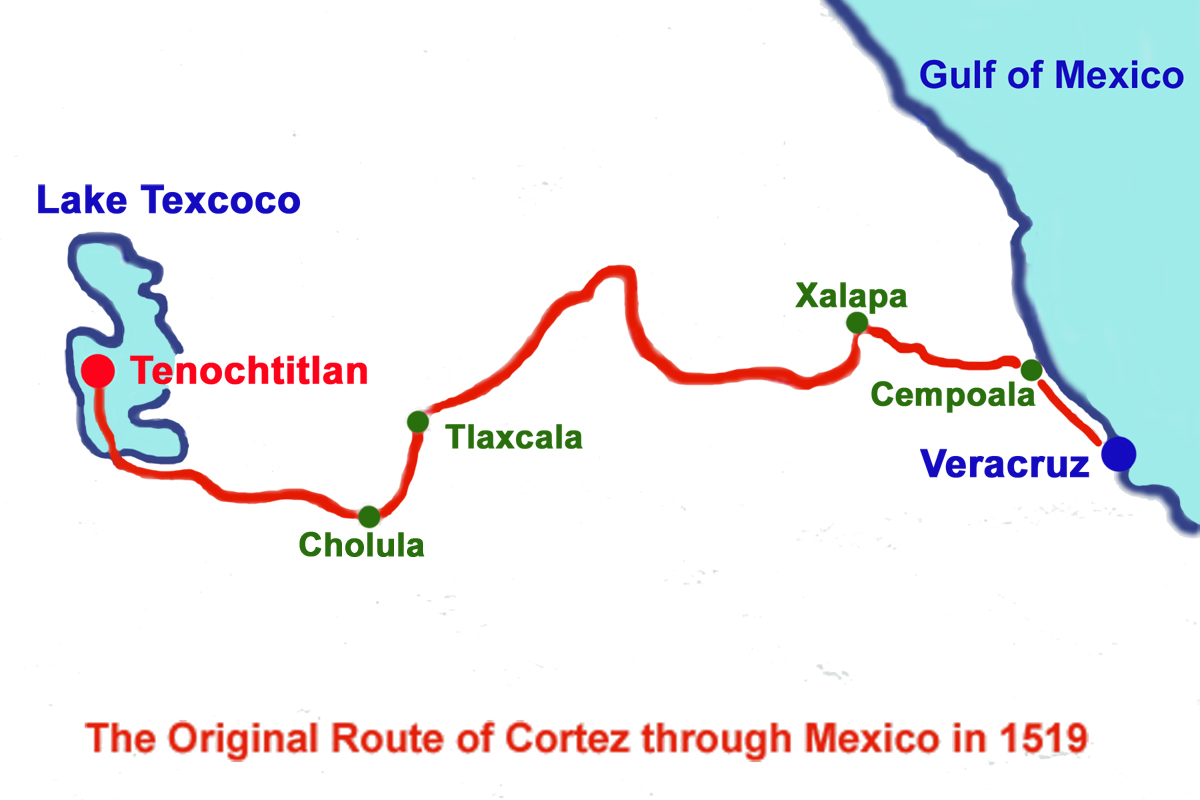

Hernando Cortez and the Conquistadors The European discovery of America by Christopher Columbus in 1492 led to the exploration and colonization of the entire Caribbean by the Spaniards. The Conquistadors, much like the Crusaders, were variably in search of fortune, personal glory, and God, and often all three. The Spaniard Hernando Cortes landed on the Gulf shore of Mexico on Good Friday, April 22, 1519. According to one of his men, Bernal Diaz del Castillo, who recorded the events of the expedition, Cortes arrived with 508 soldiers on eleven ships, 100 sailors, 16 horses, a few cannons, crossbows and other pieces of artillery. They named the landing site Veracruz, "The True Cross." Their Chaplain, Father Bartolome de Olmedo, performed Mass on Easter Sunday. Cortes worked alongside his men to build a fort and left a contingent to protect the new settlement. He then sent one ship back to Spain with a letter that detailed their discovery for King Charles V. In an historic move to strengthen their resolve to conquer the land, Cortes burned his last ten ships in the harbor, cutting off any avenue of retreat. 4 Three reasons have been given for the conquest of Mexico by this small but formidable force. The arrival of the Spanish conquistadors with their metal breastplates, snorting horses, loud smoking guns, and vicious dogs proved a frightening spectacle to the Indians. Cortes, through the Indian interpreter Dona Marina, cleverly won over outlying Indian tribes, such as the Tlaxcalans, who resented the heavy tribute demanded by the Aztecs. In addition, the Aztecs and others had no immunity to smallpox brought to American shores by the Europeans, and were decimated in a smallpox epidemic that began in 1520. 8

The expedition first went up the coast to Cempoala, where the heavily taxed tribe pledged their allegiance to Cortes. They continued through Jalapa, and headed towards Tlaxcala. They continued to find evidence of human sacrifice everywhere they went. This only strengthened their determination to stop the diabolic practice. At first the Tlaxcalans resisted the Spaniards. Cortes fought right alongside his men and forever earned their respect. Unable to defeat the Spaniards, the fierce Tlaxcalans finally joined forces with Cortes, and ultimately proved to be most valuable allies. On the way to Tenochtitlan, Montezuma planned a trap in Cholula for Cortez, but the Spaniards and the Tlaxcalans overwhelmed the Chululan tribe, allies of the Mexica, and left 3000 dead. Montezuma recalled the dream of his sister when he learned that a black cross adorned the helmets of the Spaniards. Because he believed that he was the returning god Quetzelcoatl, Montezuma refused to attack Cortes, and actually welcomed him on his arrival into Tenochtitlan 8 November 1519, and housed the Spaniards in the palace of Montezuma's father. The Spaniards were appalled at the horrible spectacle of human sacrifice, and Cortez asked Montezuma to stop. But sacrifice of adults and even children continued, and the Spaniards were awakened each morning by the screams of sacrificial victims. Cortez boldly placed Montezuma under house arrest one week after his arrival, and confined him to his palace. Montezuma presented many gifts of gold, silver, and jewels to Cortez, but would not stop the demonic rituals. Finally, Cortes climbed the stairs of the main temple, had the priests remove the Aztec gods, and placed a Cross and image of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Father Olmedo said Holy Mass.

The Aztec rituals stopped for three months. War was about to begin. Soon afterwards, Cortes had to leave the city for political reasons, and placed Pedro de Alvarado in charge of Tenochtitlan. During the festival of the sun god Huitzilopochtli in the spring of 1520, Alvarado decided to surround the Aztecs during their ritual ceremony in the temples, and slaughtered the unarmed celebrants. Outraged at this violation, the Mexica rose up in arms. Montezuma's brother Cuitlahuac assumed leadership and fiercely attacked the Spaniards. Montezuma died in the battle. Cortes returned to Tenochtitlan to find the city in open warfare. The Spaniards and Tlaxcalans were soundly defeated and driven from the city on the Night of Sorrow, June 30, 1520. However, Cortes returned to Tenochtitlan in May of 1521 with a massive army of native Indians, mostly Tlaxcalans. They were surprised to find half the population had died of a smallpox epidemic, including King Cuitlahuac. The new leader Cuauhtemoc fought Cortes for 93 days, but had to surrender the city on August 13, 1521. The once glorious city of Tenochtitlan was destroyed, and with it, the Aztec practice of human sacrifice. The conquest of Mesoamerica was complete. 4

The Early Church in Mexico Cortes' first action as conqueror was to place the region under the Spanish crown and demolish the temples of sacrifice and build Catholic churches in their place, such as the Church Santiago de Tlatelolco on the site of the Temple of the sun god in present-day Mexico City. Cortez did call for missionaries to convert the native Indians, and shortly after the Conquest, the Franciscan Peter Ghent from Belgium arrived in New Spain in August of 1523. He become known as Fray Pedro de Gante, and adopted the ways of the Indians and lived a life of poverty among the natives. He learned Nahuatl, the native Aztec language, and soon appreciated that communication with the natives was through images, music, and poetry. He first began to educate the young, and the natives soon learned to trust him and listen to the Christian message. In May of 1524, twelve Franciscan missionaries arrived, including Father Toribio Paredes de Benevente, who affectionally became known as Motolinia or "poor one" by the natives for his self-sacrificing ways. Many of the others attempted conversion by formal catechetical methods through translators. But they found the natives highly resistant to Christianity, the religion of the Conquistadors, who had killed thousands of Indians, raped their women, and destroyed Tenochtitlan. The Dominicans, including Father Bartolome de las Casas of the West Indies, the first priest ordained in the New World, the Augustinians, and the Jesuits arrived considerably later. In 1528 Charles V of Spain sent a group of five administrators known as the First Audience to govern Mexico. The First Audience was headed by Don Nune de Guzman, who quickly proved cruel and ruthless in his treatment of the native population. He forced the native population either to abandon their villages or be reduced to slavery, branded them on the faces, and sold them in exchange for cattle. To offset the First Audience, Charles V appointed Fray Juan Zumarraga as the first Bishop of Mexico City and Protector of the Indians in December of 1528. He accomplished much in his 25 years as Bishop, which included the establishment of the first grammar school, library, printing press, and the first college, Colegio de la Santa Cruz at Tlatelolco. However, he spent much of his first year in Mexico objecting to the ruthless treatment of the Indians by de Guzman, who by then had sold 15,000 Indians into slavery. The First Audience applied strict censorship, and forbade both Indians and Spaniards from bringing complaints to the Bishop. The Bishop countered with stern sermons against their use of military force, torture, and the imprisonment of Indians. Finally, in 1529, some Indians managed to smuggle a protest to Bishop Zumarraga concerning the heavy taxes and slave conditions in nearby Puebla. Bishop Zumarraga managed to send a message hidden in a crucifix back to Spain, and de Guzman was recalled. A Second Audience was appointed which proved judicial to the Indians, but did not arrive in Mexico until 1531. However, the Conquistadors and the First Audience had done grave damage to their relationship with the native population. The Indians were fed up with Spanish occupation, and resentment had reached a flash point. Isolated outbreaks of fights with the Spaniards had become inevitable, and Bishop Zumarraga feared a general insurrection. Such was the setting when the event of Tepeyac took place.

THE APPARITION Sources The following account of the five apparitions in three days is based on the oldest written record of the miracle of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the Nican Mopohua, written in Náhuatl about 1540 by Don Antonio Valeriano, one of the first Aztec Indians educated by the Franciscans at the Bishop's Colegio de la Santa Cruz. An illustration of the apparition event with the signature of Don Antonio Valeriano and the date 1548 was recently uncovered in a private collection in 1995, now referred to as the Codex 1548. The Codex 1548 has been scientifically determined to be genuine, and substantiates the historical basis of the apparition of Guadalupe. 1, 3, 7, 9-11 The Jesuit Father Miguel Sanchez published the first Spanish work on Guadalupe, Imagen de la Virgen Maria Madre de Dios de Guadalupe in 1648. Brother Luis Lasso de la Vega published in Náhuatl the Nican Mopohua and other documents in a collection known as Huey Tlamahuezoltica in 1649. The theologian Luis Becerra Tanco published his work on the tradition of Guadalupe in 1675. Finally, the Jesuit professor of theology Francisco de Florencia produced his account of the apparition in 1688. These four writers have been important in the preservation of the tradition of Our Lady of Guadalupe.1-3 The tradition of the event is of prime importance. The precipitous conversion of over 8 million Aztec Indians to Catholicism in seven years is highly indicative of the miracle of Guadalupe. It has been pointed out that great historical movements do not result from non-events. 9

The Miracle of Tepeyac The Aztec Indian Cuauhtlatoatzin, which means "the one who speaks like an eagle," was born in 1474. He married a girl named Malitzin, and they lived with an uncle near Lake Texcoco. The three were among the few to be baptized in the early days, most likely by Father Toribio in 1525, and given the names Juan Diego and Maria Lucia, and the uncle Juan Bernardino. Maria Lucia was childless, and died a premature death in 1529. Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin was a widower at age 55, and turned his life to God. It was his custom to attend Mass and catechism lessons at the Church in Tlatelolco. At daybreak, on Saturday, December 9, 1531, Juan Diego began his journey to Church. As he passed a hill named Tepeyac, on which once stood a temple to the Aztec mother god Tonantzin, he heard songbirds burst into harmony. Music and songbirds presaged something divine for the Aztec. The music stopped as suddenly as it had begun. A beautiful girl with tan complexion and bathed in the golden beams of the sun called him by name in Náhuatl, his native language, "Juan Diego!" The girl said: "Dear little son, I love you. I want you to know who I am. "I am the Virgin Mary, Mother of the one true God, of Him who gives life. He is Lord and Creator of heaven and of earth. I desire that there be built a temple at this place where I want to manifest Him, make him known, give Him to all people through my love, my compassion, my help, and my protection. I truly am your merciful Mother, your Mother and the Mother of all who dwell in this land, and of all mankind, of all those who love me, of those who cry to me, and of those who seek and place their trust in me. Here I shall listen to their weeping and their sorrows. I shall take them all to my heart, and I shall cure their many sufferings, afflictions, and sorrows. So run now to Tenochtitlan and tell the Lord Bishop all that you have seen and heard."

Juan Diego went to the palace of the Franciscan Don Fray Juan de Zumarraga, and after rude treatment by the servants, was granted an audience with the Bishop. The Bishop was cordial but hesitant on the first visit and said that he would consider the request of the Lady and politely invited Juan Diego to come visit again. Dismayed, Juan returned to the hill and found Mary waiting for him (second apparition). He asked her to send someone more suitable to deliver her message "for I am a nobody." She said on this second visit, "Listen, little son. There are many I could send. But you are the one I have chosen for this task. So, tomorrow morning, go back to the Bishop. Tell him it is the ever holy Virgin Mary, Mother of God who sends you, and repeat to him my great desire for a church in this place." So, Sunday morning, December 10, Juan Diego called again on the Bishop for the second time. Again with much difficulty, he was finally granted an audience. The Bishop was surprised to see him and told him to ask for a sign from the Lady. Juan Diego reported this to the Virgin (third apparition), and she told him to return the following morning for the sign. However, when Juan Diego returned home he found his uncle Juan Bernardino gravely ill. Instead of going back to Tepeyac, he stayed home with his dying uncle on Monday. Juan Diego woke up early Tuesday morning, December 12th, to bring a priest from the Church of Santiago at Tlatelolco, so that his uncle might receive the last blessing. Juan had to pass Tepeyac hill to get to the priest. Instead of the usual route by the west side of the hill, he went around the east side to avoid the Lady. Guess who descended the hill on the east side to intercept his route! The Virgin said, "Least of my sons, what is the matter?" Juan was embarrassed by her presence (fourth apparition). "My Lady, why are you up so early? Are you well? Forgive me. My uncle is dying and desires me to find a priest for the Sacraments. It was no empty promise I made to you yesterday morning. But my uncle fell ill." Mary said, "My little son. Do not be distressed and afraid. Am I not here who am your Mother? Are you not under my shadow and protection? Am I not the fountain of your joy? Are you not in the fold of my mantle, in the cradle of my arms? Your uncle will not die at this time. This very moment his health is restored. There is no reason now for your errand, so you can peacefully attend to mine. Go up to the top of the hill; cut the flowers that are growing there and bring them to me." Flowers in December? Impossible, thought Juan Diego. But he was obedient, and sure enough found beautiful Castilian roses on the hilltop. As he cut them, he decided the best way to protect them against the cold was to cradle them in his tilma - a long, cloth cape worn by the Aztecs, and often looped up as a carryall. He ran back to Mary and she rearranged the roses and tied the lower corners of the tilma behind his neck so that nothing would spill, and said, "You see, little son, this is the sign I am sending to the Bishop. Tell him that now he has his sign, he should build the temple I desire in this place. Do not let anyone but him see what you are carrying. Hold both sides until you are in his presence and tell him how I intercepted you on your way to fetch a priest to give the Last Sacraments to your uncle, how I assured you he was perfectly healed and sent you up to cut these roses, and myself arranged them like this. Remember, little son, that you are my trusted ambassador, and this time the Bishop will believe all that you tell him." This fourth apparition was the last known time Juan Diego ever saw the Virgin Mary. Juan called for the third time on the Bishop and explained all that had passed. Then Juan put up both hands and untied the corners of crude cloth behind his neck. The looped-up fold of the tilma fell; the flowers he thought were the precious sign tumbled out on the floor. The Bishop rose from his chair and fell on his knees in adoration before the tilma, as well as everyone else in the room. For on the tilma was the image of the Blessed Virgin Mary just as described by Juan Diego. While Juan Diego was calling on the Bishop, Juan Bernardino, the dying uncle, suddenly found his room filled with a soft light. A luminous young woman filled with love was standing there and told him he would get well. During this fifth apparition, she told him that she had sent his nephew, Juan Diego, to the Bishop with an image of herself and said, "Call me and call my image Our Lady of Guadalupe."

THE IMPACT The news of the appearance of the Indian mother who left her imprint on the tilma spread like wildfire! Three points were appreciated by the native population. First, the lady was Indian, spoke Náhuatl, the Aztec language, and appeared to an Indian, not a Spaniard! Second, Juan Diego explained that she appeared at Tepeyac, the place of Tonantzin, the mother god, sending a clear message that the Virgin Mary was the mother of the true God, and that the Christian religion was to replace the Aztec religion. And third, the Indians, who learned through pictures and symbols in their culture of the image, grasped the meaning of the tilma, which revealed the beautiful message of Christianity: the true God sacrificed himself for mankind, instead of the horrendous life they had endured sacrificing humans to appease the frightful gods! It is no wonder that over the next seven years, from 1531 to 1538, eight million natives of Mexico converted to Catholicism! 1-3, 7, 9-11

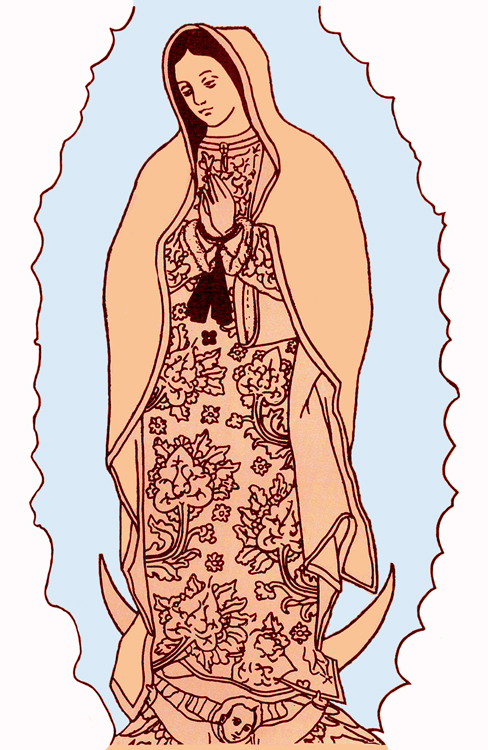

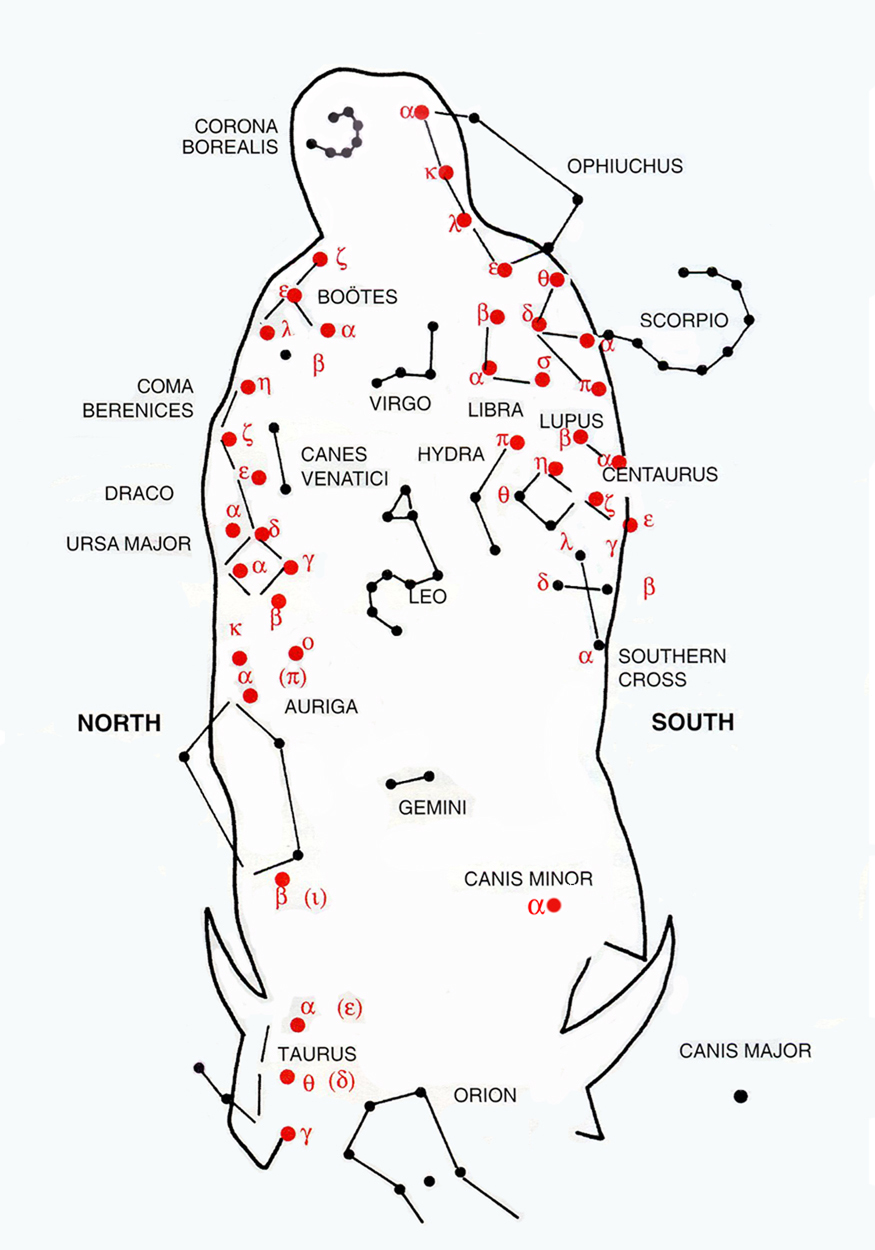

The Image on the Tilma The imprint of Mary on the tilma is striking, and the symbolism was primarily directed to Juan Diego and the Aztecs. Mary appears as a beautiful young Indian maiden with a look of love, compassion, and humility, her hands folded in prayer in reference to the Almighty God. Her rose dress, adorned with a jasmine flower, eight petal flowers, and nine heart flowers symbolic to the Aztec culture, is that of an Aztec princess. Her blue mantle symbolized the royalty of the gods, and the blue color symbolized life and unity. The stars on the mantle signified the beginning of a new civilization. La Morenita appeared on the day of the winter solstice, considered the day of the sun's birth; the Virgin's mantle accurately represents the 1531 winter solstice! Mary stands in front of and hides the sun, but the rays of the sun still appear around her, signifying she is greater than the sun god, the greatest of the native divinities, but the rays of the sun still bring light. Twelve rays of the sun surround her face and head. She stands on the moon, supported by an angel with wings like an eagle: to the Aztec, this indicated her superiority to the moon god, the god of night, and her divine, regal nature.

Most important are the black maternity band, a jasmine flower, and a cross that are present in the image. Mary wore a black maternity band, signifying she was with child. At the center of the picture, overlying her womb, is a jasmine flower in the shape of an Indian cross, which is the sign of the Divine and the center of the cosmic order to the Aztec. This symbol indicated that the baby Mary carried within her, Jesus Christ, the Word made Flesh, is Divine and the new center of the universe. On the brooch around her neck was a black Christian cross, indicating she is both a bearer and follower of Christ, the Son of God, our Savior, who died on the Cross to save mankind In summary, the image signified Mary bringing her Son Christ to the New World through one of their own!1-3, 7, 9-11

One cannot help but identify Our Lady of Guadalupe with the Woman of the Apocalypse.1, 12 "A great sign appeared in the sky, a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon at her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars." Revelation 12:1

The tilma itself was a cape worn by the Indians of the time, made of ayate, a coarse fiber from agave or the maguey plant. The cape measures 5.5 x 4.6 feet, and is made in two parts sewn by a vertical seam made with thread of the same material. The natural life of the fiber is roughly 30 years, yet the tilma and the image remain intact after 470 years, in spite of moisture, handling, and candles! 1, 2, 10

The Immediate Aftermath Bishop Zumarraga was overwhelmed by the miracle of the tilma, and this time extended his hospitality to Juan Diego and invited him to spend the night. He gently removed the tilma and placed it in his private chapel, where all prayed in thanksgiving for the miracle. The following day, they set out for Tepeyac, and Juan Diego showed Bishop Zumarraga where Mary had appeared. The Bishop directed that a small chapel be erected at the site. The enthusiasm from the event produced so many volunteers that a chapel in Tepeyac was constructed by Christmas Day. Juan Diego then asked leave of the Bishop that he might see his uncle. The Bishop insisted that Juan Diego be escorted back to his home and then returned to his palace. Juan Diego and Juan Bernardino were joyfully reunited, and both recounted to each other the miraculous events. Juan Diego brought his uncle back to the Bishop's residence to show him the tilma, and they stayed as guests of the Bishop until Christmas. The convergence of the curious multitude led the Bishop to move the tilma to the Cathedral so that all could marvel and pray. On December 26, 1531, a solemn procession with the Bishop, Juan Diego, Franciscan priests, and the faithful brought the tilma from the Cathedral to the Chapel at Tepeyac. Thousands attended the procession. In the excitement, some Indians shot arrows into the air, and one mortally wounded a man in the procession. A priest tended to the wound, and prayers were said to the Virgin, and the man was reported to have been miraculously healed. This only added to the fervor of the procession. Juan Diego lived in a hermitage built for him next to the chapel at Tepeyac, and showed the tilma and explained the apparition and its Christian significance over and over to pilgrims who visited the shrine. He died peacefully on May 30, 1548 and was buried at Tepeyac. Bishop Zumarraga died only three days after Juan Diego. The miracle of Our Lady of Guadalupe led to a tidal wave of conversions. The few missionaries that initially were met with resistance became overwhelmed with baptisms, preaching, and instruction in the faith. An early missionary, the Franciscan Father Toribio de Benavente, recorded in his Historia de los Indios, published in 1541, that "I have to affirm that at the convent of Quecholac, another priest and myself baptized 14,200 souls in five days. We even placed the Oil of Catechumens and Holy Chrism on all of them." 2

Recent Developments The Virgin of Guadalupe is literally intertwined with both the History of the Catholic Church in the new world and of Mexico itself. To mention a few events, the great floods of 1629 claimed 30,000 lives and threatened the destruction of the valley of Mexico, until the waters abated when the image was taken in solemn procession from Tepayac to Mexico City. A horrible plague in the early 1700s claimed the lives of 700,000 people, and, once the Virgin of Guadalupe was declared the Patroness of Mexico on 27 April 1737, the disease dissipated. But before that, as Mexico became mestizo, the union of Spanish born in Mexico and the Indians, La Morenita, or the dark Virgin, became the symbol of the people, and they love her as one of their own. 6, 7 On November 14, 1921, during a period of government persecution, a powerful bomb hidden in flowers exploded directly underneath the tilma during High Mass, and destroyed stone and marble in the sanctuary and shattered the stained-glass windows of the Basilica. When the smoke cleared, the congregation was amazed to find that the tilma remained untouched, and the thin protective glass covering was not even cracked, nor was anyone hurt. Scientific studies of the tilma have been undertaken through the years, which have only served to confirm its supernatural nature. The tilma remains just as vibrant as ever, having never faded. Famous Mexican artists such as Miguel Cabrera (1695-1768) determined that it is impossible for the rough surface of the tilma to support any form of painting. Furthermore, the tilma appeared to embody four different kinds of painting, oil, tempura, watercolor, and fresco, blended in an inexplicable fashion. One of the unusual characteristics of the tilma is that up close the features are unremarkable, but the tone and depth emerge beyond six or seven feet and the image becomes more radiant and photogenic. The astonishing discovery that reflections of people in Mary's eyes, perhaps Juan Diego and Bishop Zumarraga or the interpreter Juan Gonzalez, were confirmed by two scientists in 1956. This phenomenon is seen only with human eyes, not in a painting.2, 10, 11 Studies by infra-red photography in May of 1979 were undertaken by Philip C. Callahan, a research biophysicist at the University of Florida. He ruled out brush strokes, overpainting, varnish, sizing, or even preliminary drawings by an artist in the body of the image. Damage from the 1629 flood was apparent at the edges of the tilma. He concluded that the original image on the tilma has qualities of color and uses the weave of the cloth in such a way that the image could not be the work of human hands.10, 11 How did Our Lady identify herself? Bishop Zumarraga understood the Spanish name Guadalupe, a Marian shrine in Estremadura, Spain. But Mary spoke Nahuatl to Juan Diego, and some writers suggest that she may have said Coatlaxopeuh or one "who treads on the snake," recalling Genesis 3:15. On the other hand, Juan Gonzalez, the interpreter present for conversations between Juan Diego, his uncle, and the Bishop, was reported to be fluent in both Nahuatl and Spanish, so any misinterpretation would seem unlikely.2, 4 Either may be possible, as Mary is our Mother (John 19:25-27) everywhere. The tilma of Juan Diego is the only known divine image of the Blessed Virgin Mary that exists on our planet! Seven million people from the Americas visit the Virgin of Guadalupe every year, especially on December 12, the annual celebration of the miracle. If one visits Mexico City, one can plainly see who has the heart of the people. One finds the Virgin of Guadalupe pictured everywhere in Mexico City, in the airport, taxis, bakeries, even on streetcorners. Our Lady has been the factor that has preserved the Aztec Indians from the cultural disintegration observed with other Indian populations such as in North America.3 Popes through the ages have recognized Our Lady of Guadalupe, and Pope John XXIII was the first to call the Virgin Mother of the Americas on October 12, 1961. John Paul II was the first Pope to visit the Guadalupe shrine on January 27, 1979. On January 23, 1999, Pope John Paul II, referring to all of the Americas as one single continent, called the Virgin of Guadalupe the Mother of America. Pope John Paul II canonized Juan Diego a Saint on July 31, 2002. Juan Diego certainly deserves sainthood, as he was both humble and obedient to the request of Our Lady. The Catholic Church remains firmly entrenched in Mexico, Central and South America, which today are at least 90% Catholic. The Catholic Church of the United States with 60 million Catholics can attribute much of our recent growth to the Hispanic population of North America. Dios te salve, María, llena eres de gracia, El Señor es contigo. Bendita tú eres entre todas las mujeres, y bendito es el fruto de tu vientre, Jesús.

Santa María, Madre de Dios, ruega por nosotros pecadores, ahora y en la hora de nuestra muerte. Amén.

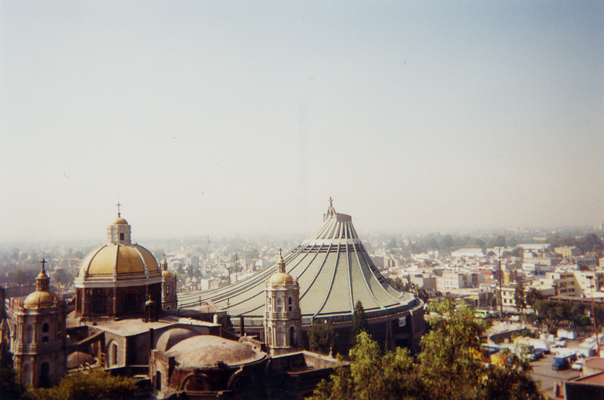

Friday, December 12, 2003 La Basilica de la Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe I write this from Mexico City during the Feast Day of Our Lady of Guadalupe. The Mexico Herald reports that a crowd of 5 million has come to honor the Blessed Virgin Mary in Tepeyac, now La Villa, Mexico City. The square in front of the Basilica is filled with families waiting to attend Mass and to see the tilma of St. Juan Diego. The beautiful new Basilica, which holds 10,000 people, was completed in 1976. I am struck by the faith of the Mexican people. Some are walking on their knees, some circle in native dances. Some have travelled for three days and have camped out in front of the Church. They line up in front of the escalators that go underneath the tilma behind the main altar. They pray and cry in front of the beautiful relic of the Virgin that visited their land 472 years ago. I look up and am struck by the natural beauty and colors of the Virgin's dress. How can the tilma be so bright but so old?! The paintings in the nearby museum are only 150 years old but are dark and faded. The Mass of the Roses blends all of the Mexican cultures - Indian, Criollo, and Mestizo. The music is interspersed with the beat of native drums and dancing. The crucified Jesus hangs alone on his cross above the main altar, which is elevated on a platform. Behind the altar to the right is the tilma of the Virgin, underneath a large cross on the wall. The aroma of roses fills the air. Love and tears fill the faces of the people. Our Lady of Guadalupe, Patroness of the Americas, please pray for us. LMH

REFERENCES 1 Testoni, Manuela. Our Lady of Guadalupe - History and Meaning of the Apparitions . St. Paul - Alba House, Staten Island, New York, 2001. 2 Johnston, Francis. The Wonders of Guadalupe, or El Milagro de Guadalupe . Tan Books and Publishers, Rockford, Illinois, 1981, 1996 (Spanish). 3 Demarest D, Taylor C. The Dark Virgin - The Book of Our Lady of Guadalupe . Coley Taylor Publishers, Freeport, Maine, 1956. 4 Carroll, Warren H. Our Lady of Guadalupe and the Conquest of Darkness. Christendom Press, Front Royal, Virginia, 2002. 5 Boone, Elizabeth. The Aztec World. St. Remy Press and the Smithsonian Institution Books, Washington, D. C., 1994. 6 Krauze, Enrique. Mexico - Biography of Power . Harper-Collins Publishers, New York, 1997. 7 Elizondo, Father Virgilio. La Morenita - Evangelizer of the Americas . Mexican American Cultural Center, San Antonio, Texas, 1980. 8 Berkin C, Miller CL, Cherny RW, Gormly JL. Making America, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 2007. 9 Schreck, Alan. Historical Foundations. Franciscan University, Steubenville, Ohio, 2003. 10 Anderson, Carl and Monsignor Eduardo Chavez. Our Lady of Guadalupe - Mother of the Civilization of Love. Doubleday, New York, 2009. 11 Rengers, Christopher OFM. Mary of the Americas . St. Paul - Alba House, Staten Island, New York, 1989. 12

Navarre RSV Bible. Four Courts Press, Dublin, Ireland, 2005. |

[ Home ] [ Messages

and Signs ] [ In Defense of the Truth ] [ Saints

] [ Pilgrimages ] [ Testimonies

] [ Ordering ]