[ Home ] [ Messages and Signs ] [ In Defense of the Truth ] [ Saints ] [ Pilgrimages ] [ Testimonies ] [ Ordering ]

|

Our

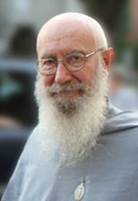

Lady of Guadalupe Fr. Peter Damian Fehlner, F.I., a member of the Franciscans of the Immaculate, is an internationally known lecturer on Marian doctrine who has appeared on EWTN and is past editor of the international Marian magazine founded by St. Maximilian Kolbe, Miles Immaculatae. This article first appeared in the publication A Handbook on Guadalupe, Academy of the Immaculate, 1997. Published

on December 2, 2011 by Fr.

Peter Damian Fehlner

in December

2004,

Marian

Private Revelation Is

there a link between Guadalupe and the Immaculate Conception? From the

time of the apparition and first glimpse of the Miraculous Image on the

tilma of Bl. Juan Diego, Catholics, Spaniards and Indian, American and

European, have always believed there is a relation between Mary Immaculate

and Guadalupe. But

toward the end of the “age of enlightenment,” the eighteenth century,

voices increasingly more strident have denied any such connection.

Clearly, these “voices” are often identical with those who doubt or

deny the historicity and/or supernatural nature of the apparitions. The

arguments they use and the conclusions they reach exactly parallel those

of modernists who claim one can deny the historicity of the infancy

narratives, but still believe as a Catholic in the “symbolic” value of

Marian dogmas such as the divine motherhood and perpetual virginity. As

so frequently happens, those attacking the truths of Faith unwittingly

draw the attention of believers to the importance of facts easily

discovered, yet commonly overlooked, which justify the traditional belief.

In this case it is the role played by the Franciscans who assured that the

link, intended by Our Lady, would be seen. That link has been explained

over the centuries to rest upon the Franciscan influence in Spain and the

New World. During

the first two hundred years after the apparition, belief in a link between

Guadalupe and the Immaculate Conception usually is evident in discussions

of the “Woman clothed with the sun” (Apoc. 12,1 ff) plainly recalled

by the Miraculous Figure of the Mother of God on the tilma. By 1531 it was

commonplace among Catholics to identify the Woman of the Apocalypse the

Woman who crushes the head of the serpent (Gen. 3,15), with the Mother of

God, Coredemptrix and Queen, under the title of Immaculate Conception. The

popular awareness of that identity and of its significance is the result

of the role played by the Franciscan Order. It was the Franciscan

theologian, Bl. John Duns Scotus (1266?-1308), who worked out the classic

theology of the Immaculate Conception. Since then, Franciscan preachers

and missionaries, guided by his profound insights, effectively contributed

to the acceptance of his “thesis” throughout the Church. A good

example of this kind of “borrowing Franciscan insights” without

mentioning the Franciscans, is to be found in the writings of the Mexican

Miguel Sanchez (1594-1674). As long as one is aware of and accepts the

assumptions of the Franciscan “thesis” about the Immaculate, then the

reference to the text of the Apocalypse mirrored on the tilma clearly

says: She is the Immaculate Woman. More

recently, defenders of the tradition have brought forward arguments based

on the words which our Lady used to identify herself to Juan Bernardino.

Thus, Helen Behrens popularized the view that in identifying herself Our

Lady used, not the Spanish name Guadalupe, but a word in Nahuatl: Coatlaxopeuh,

i.e., I am the one who has crushed the head of the serpent (who demands

human sacrifice). To Spanish ears that word spoken by Juan Bernardino

would have sounded like Guadalupe; whence the link with the Spanish

shrine and the popular name of the Mexican shrine. Now,

the meaning assigned Coatlaxopeuh in this thesis (crushing the head

of the serpent) has come under considerable fire from students of Nahuatl

and of Aztec culture. The sometimes heated exchanges, concentrating on

what is a secondary point in regard to our theme, distract from the

essential contribution of Helen Behrens. She called the attention of the

English speaking public to some true facts. First,

Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico really is the Immaculate, the “Perfect

Virgin” of the Nican Mopohua. In bringing about the conversion of

nations to Jesus she does in some real sense crush the head of the enemy

of the Savior and our salvation, whatever form this opposition takes. She,

the Mother of mercy, because she is the Immaculate, intervenes in history

to secure the conversion, sanctification and salvation of all peoples. Second,

Coatlaxopeuh, the word used by Juan Bernardino, whatever it means

in Nahuatl when pronounced does sound like Guadalupe in Spanish!

But to say that the link between Guadalupe and the Immaculate is based

only on the misunderstanding of the word Guadalupe is a capital error.

This fails to take into account the role played by the Franciscans at both

Guadalupan shrines. By

the end of the fifteenth century the Franciscans had placed in the shrine

of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Extramadura a statue of the Immaculate

Conception, one which soon became a popular object of veneration. There is

also good evidence that the same statue had already been made known by the

Franciscan missionaries in Mexico to the Indians and that perhaps a

reproduction was already venerated in the vicinity of Tepeyac. Now,

the similarity between the depiction of the Immaculate in the statue

placed by the Friars Minor in the sanctuary of Extramadura and the Image

on the tilma is extraordinarily close, so close that anyone from the

region of Extramadura, like the Spanish translator in the Bishop’s

palace, hearing what sounded like Guadalupe, would have spontaneously

associated this Image with the Immaculate Conception statue in Spain. In

the Franciscan tradition the Immaculate is Our Lady, Queen of the Angels,

whose Portiuncula (Little Portion) was the chapel where Angels were

often seen to descend and ascend, waiting on their Queen and her clients,

“the rest of her offspring,” i.e., the rest of the Savior’s brethren

(cf. Apoc. 12:17). This is the place where St. Francis came to understand

his vocation, found his Order and where he died. When,

therefore, the good Bishop beheld the roses spilling on the floor, it was

not only a sign that he could believe Juan Diego, but an answer to his own

prayer for a sign assuring the success of the evangelization and the

pacification of the two peoples. When he saw the image of Our Lady

supported by an angel at her feet on the tilma, he could not help but

recognize the Franciscan mode of conceiving the Immaculate as Queen of the

Angels. The link between Guadalupe in Mexico, Guadalupe in Spain and the

Immaculate Conception was fixed. The core of the Perfect Virgin’s

message at every authenticated appearance since, because she is the

Immaculate, rests upon her maternal mediation as Dispenstrix of God’s

mercy and grace. It is she upon whom the Angels wait, the Angels venerated

at both Guadalupe shrines. The

association between Guadalupe in Mexico and the Immaculate Conception was

perceived immediately, not only in Mexico, but in Europe as well. More and

more as the Miracle came to be known representations of the Immaculate

Conception reflected the likeness on Bl. Juan Diego’s tilma. With the

decisive victory of the Christian fleet over the more powerful Moslems at

Lepanto, lifting the threat of the infidels over the whole of Europe,

through a copy of the Icon, the Immaculate Conception came to occupy

center stage in the Catholic counter-reformation. She is the

Auxiliatrix Christianorum—Help of Christians. This,

therefore, is what the tradition uniformly assumed. To get around the

obvious, skeptics interpreted references to the Woman of Apocalypse, such

as those of Miguel Sanchez, the seventeenth century commentator, as

inspired by criollo patriotism, rather than as they always have

been understood: testimonials to the common belief in the Immaculate

Conception reflected by the Image on the tilma. There is no indication

that Sanchez or Bl. Juan Diego or our Lady anticipate a liberation

theology interpretation of the Magnificat. The proof is all to the

contrary. The

role of Franciscan piety in the origins of Guadalupe is understandable in

the context of the Franciscan influence in Spain and Mexico, an influence

explicitly and almost aggressively “Immaculatist.” At the time of the

apparitions the Franciscan Order was popularly known as the one which

“preached the Immaculate Conception.” Our Lady appearing at Tepeyac

made use of Franciscans and their long tradition of devotion to the

Immaculate, first of all in the person of Bishop Zumárraga, who openly

supported the building of the first church at the site which she

indicated. The

Franciscan spirituality, plus the urgency of the times, inspired and

impelled Christopher Columbus, a Third Order Franciscan, in his

expeditions. He was quite familiar with the Apocalypse, in particular

chapter 12, with its account of the opening of the Ark of the Covenant in

heaven and the appearance of the Woman clothed with the sun, who literally

is the Ark. This is the same biblical reference which played so central a

role in the iconography of the tilma. There Our Lady blots out the sun,

indicating she is greater than the sun god whom the Aztecs worshiped. She

has the moon beneath her feet and stars on her robe which places her above

and beyond mere terrestrial creation. Guadalupe

is not an explanation of the Immaculate Conception as such. Rather it is a

heavenly confirmation of the basis for her universal maternal mediation as

the Immaculate One, and so provides the key to the understanding of the

successful evangelization of Mexico and of all people and nations. It is

no accident that in every authentic appearance of our Lady since 1531, in

some way these two themes, Immaculate Conception and Marian mediation, are

involved. In a word, the appearance of the Perfect Virgin declares

the wonders of divine grace and glory over a world darkened by sin, the

degradation of false worship involving human sacrifice, and the

enslavement of neighbor through unjust amassment of riches. Similarly,

today vast numbers of souls are enslaved by the idolatry of sensual

pleasure. Instead of worshiping the Child of the Virgin as Our Lady of

Guadalupe asked, they sacrifice their offspring and their fecundity to the

demands of lust and greed. How needed it is to look upon and listen to the

Mother of Tepeyac, the Mother of Life and heed her requests to build a

temple for the Holy Spirit in their souls in imitation of the Immaculate

Virgin’s purity, modesty and chastity. Guadalupe,

then, is no mere symbolic myth as one prestigious anti-apparitionist

claims and this book refutes. Guadalupe is above all a person, the Perfect

Virgin, our Mother of mercy, a model to be imitated, and a living

Mother who anticipates our needs as when she intervenes in our history for

the sake of our salvation and for the sake of our welfare as pilgrims in

this world. As a Mother to all she deliberately spoke in a way that both

nations, Indian and Spanish, would understand the same mystery at

Extramadura and at Tepeyac—the Immaculate Virgin in her unique role as

Mother of all men. Before

airing questions of inculturation, politics, economics, etc., there is

need for unity of Faith in her Son. This is possible only when she is

humbly acknowledged to be the Mother of God, as in Mexico, by both nations

through the erection of a temple in her honor. Where this is not

recognized, there will be constant conflict and revolution. The genius of

Catholicism, of Catholic political philosophy and culture, is the Perfect

Virgin. “Behold

your Mother” Jesus

says to St. John (Jn 19:26). To all his “beloved disciples” could He

not also be saying before the tilma of Bl. Juan Diego: Behold the Woman of

Revelation, the Immaculate? The more we grasp and live this mystery, the

foundation of the Virgin’s compassionate and motherly mediation, the

greater our understanding of the person and work of her Son and Savior,

and our sharing in His life. Blessed, indeed, those who behold their

Immaculate Mother and, as the Son asks, take her into their homes by true

devotion to Mary, by total consecration to the Immaculate. |

[ Home ] [ Messages

and Signs ] [ In Defense of the Truth ] [ Saints

] [ Pilgrimages ] [ Testimonies

] [ Ordering ]